×

By Ellen Moyer

brbrCitizens in the New World named it “The Athens of America” and visitors proclaimed it “The Bath of America.” This was pretty high praise for a small town of 1,000 recently carved out of the wilderness in a new land on the Chesapeake Bay. Athens, being one of the world’s oldest cities after all, is acclaimed as the birthplace of western civilization and democracy and a center for the arts, learning, and philosophy. By 1784, the Annapolis had lived up to this tradition.

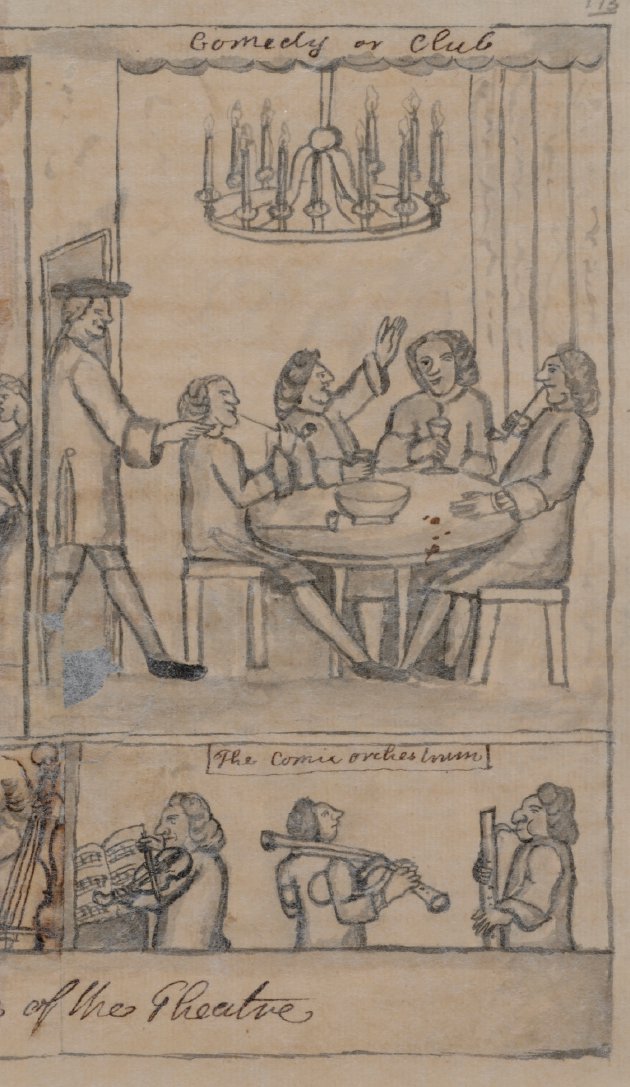

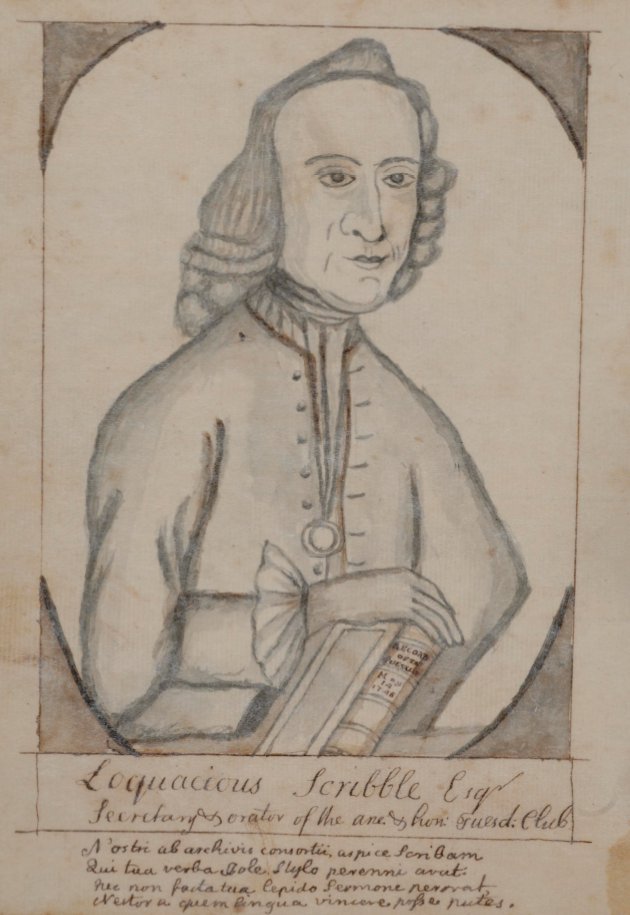

brbrBath, in England, was the most fashionable resort of the 18th century and the center of social elegance, with concerts, operas, and theater. In the Colonies, Annapolis was that resort. Bath, like Annapolis, is a city of Georgian architectural beauty. It is a World Heritage site that, today, hosts multiple international festivals for the arts. Local competitions for the best poet, singer, and storyteller awards include the “Bard of Bath.” In Colonial Annapolis, that award would have gone to Dr. Alexander Hamilton, founder in 1745 of the Tuesday Club. Dr. Upton Scott said of him “…he never failed to delight with the effusions of his wit, in which acquirements he had no equal…” Jonas Greene, the publisher of the Maryland Gazette, America’s first continuously published newspaper, might have been a good contender as well. Both were favorites of the ribaldry that occurred during the weekly meetings within the homes of the gentlemen of Annapolis, who were dedicated to wit and learning in the City’s first theater for the performing arts.

brbrIn the northern Colonies—the lands of Quakers and Puritans, who were not fans of wit— theater was viewed as a “highway to hell.” This was a holdover from the days of Puritan William Prynne, who spent seven years writing a 1,100-page book on the

evils of the theater. Published in 1632, the book asserted that all actresses were” notorious whores.” Unfortunately for him (and proving that timing dictates life’s happenings), the Queen Henrietta Maria, who gave her name to the Colony of Maryland, was rehearsing for an amateur performance of a pastoral. Prynne was fined, stood in pillory, and condemned to life imprisonment. If that wasn’t enough, he was branded on both cheeks with “SL,” for “seditious libeler,” and had his ears cut off. One hundred years later, the northern American Colonies passed laws forbidding theater productions, but, as far as is known, no one was libeled or had their ears cut off for performing in playhouses in the warehouses of the bigger cities.

brbrTheater, however, found fertile ground in Annapolis. Below the Mason Dixon line, the customs of England prevailed. Annapolis, described as more English than the English, idolized the English gentry. Reverend Jonathan Boucher, in his Reminiscences said: “I hardly know a town in England so desirable to live in as Annapolis.” The most famous men in England wrote plays and performed in them to the enjoyment of the proud aristocracy. Theater companies were family affairs. In Annapolis, theater brought refinement to the frontier city described as the “genteelest town in North America.”

brbrThe popular musical, The Beggars Opera, opened the city to performance of professional actors on June 18th, 1752. Managed by Murray and Kean, one of the first professional acting companies in the New World, they stayed in Annapolis for some time, producing performances of Cato and Richard III.

brbrWithin the decade, Kean was followed by the Hallam Company, sometimes called the first fully-professional theater to perform in North America. In the early days of theater, companies were family oriented. Adam, the Hallam patriarch, had been a respected actor at Covent Gardens in London. Four of his five sons followed in the profession. The Hallam Company, though noted for their experience and ability, however, were not making headway on the London Stage. William, the manager, decided to take a risk in America and brought the entire company of 12 performers and three children to the Colonies. And here, they made it well. In 1760, the entire summer season of theater shows was performed in Annapolis by the Hallam Company featuring Mr. John Palmer, an actor who excelled in comedy, from the Drury Lane Theatre in London.

brbrIn Annapolis, theater made the city a center for the fine arts and culture. It was so popular, that by 1771 the city, with the help of Hallam, built its own performing arts center on West Street, on land owned by the Vestry of St. Anne’s Parish. This was the first playhouse in North America built with red brick. Of it, William Eddis, author of Letters from America 1769–1777 and a government official under Governor Robert Eden, wrote, “Our new theatre…was opened to a numerous audience the week preceding the Races…the Boxes commodious and neatly decorated…performers well above mediocrity.” Tickets, sold in the coffee houses and pubs, cost seven, five, or three shillings, depending on seats. The green velvet curtains scrolled up giving us the term “curtain going up” even though, in later years, it swished sideways. Above the stage, the motto, “The Whole World Acts the Player,” was inscribed. Annapolis scored another first when the first critical opinion and detailed dramatic criticism on the performance of Cymbeline, appeared in the Maryland Gazette.

brbrAll theater ceased during the War for Independence. The Golden Age of Annapolis, the Bath of America, was over. The first-of-its-kind theater was torn down in 1818. Its corner stone saved, according to Elihu Riley, in The Ancient City, to be used a decade later, in a new Hallam Theatre. In 1829, the French Corps de Ballet opened the new 500-seat Hallam Theatre on Duke of Gloucester Street. Despite good musical programs featuring the work of Haydn, Father of the Symphony and Father of the String Quartet, the theatre struggled financially. In 1846, it was purchased by the new Presbyterian Congregation led by Dr. John Ridout and Arsene Girault, a professor at the Naval Academy. The theatre was changed to a space of worship. The Hallam Theatre, built in 1829 and still largely intact—with a cornerstone that included the town’s newspapers, the names of the building committee, and a copy of George Washington’s Will—is now and has been the First Presbyterian Church of Annapolis since July, 1847.

brbrThe next years were turbulent for the Annapolis and the nation as a whole. There was not much joy in America. After thirty years of dark nights, The Masons were the first to bring professional theater back to Annapolis. In 1873, a new Opera House opened on Maryland Avenue at the corner of Prince George Street. Nationally-known and popular performer Laura Keene packed the house. Vaudeville shows, Gilbert and Sullivan Operettas, and local amateur companies entertained Annapolitans.

brbrOn May 18, 1903, a reconstructed 18th century estate, the Woodward/Dulaney house on Main Street, became a 1,000-seat live theater. Once part of Mann’s Tavern and the elegant City Hotel, the theater’s architects used the wall panels, elegant 18th century interior elements, and the staircase that led to the second floor (that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson had walked on) in the refurbished new theater. The Evening Capital wrote, “No playhouse in America can outrival this one in history.” When the 300 lights went on “the effect was magic and the view most beautiful.” In 1918, it was all gone, burned down in a devastating fire. The Hillman Garage now occupies the site that once housed a magnificent home, tavern, and hotel with gardens and a stable for 50 horses—once familiar to the founders of our Nation and the most elegant theater in Maryland.

brbrTwo years later, Governor Albert Ritchie cut the ribbon for the new Circle Theatre on State Circle with 2,800 attendees. The Circle was a Vaudeville-style theater with dressing rooms and an orchestra pit with the best acoustics around. It had 920 seats—boxes, blue leatherette seats—and blue velvet curtains. The Beaux Art building was designed by St. Johns College-graduate Henry Powell Hopkins, who also designed the Senate Office Building in 1935. Two replica lamp posts from Washington’s time graced its entrance at the street corner book ends. Popular performers, such as Otis Skinner, played the Circle. Later in life it became a movie theater of the Durkee chain. When it was sold in 1984, a group of business leaders and legislators hoped to secure the theater as one of America’s Historic Theaters and a playhouse for historical pageants. Neither downtown residents nor Historic Annapolis embraced the idea and the building became an office building for lobbyists.

brbrColonial Players, a volunteer theatrical group, is approaching 70 years of award-winning performances. Initiated by Becky Clatanoff, whose name would adorn a building at Anne Arundel Medical Center, the Players began in 1949 to celebrate the City’s 300th anniversary. The performance of The Male Animal was staged at the abandoned USO building, and later City Recreation Center, on St Mary’s Street. Needing a permanent home, the Players found it in an old stable and auto shop at 108 East Street.

brbrRecycling old buildings seems to be a habit of Annapolis theater managers. Also needing a permanent home (after opening in the garden of the closed Carvel Hall Hotel with the Musical Brigadoon), Joan Baldwin, a visionary and creative genius who loved the challenge of making new ideas work, latched on to the abandoned Shaw Blacksmith Shop, circa 1836, located in an industrial waterfront district dating to1696, on Compromise Street. With no money but a lot of energy, actors and friends cleaned out old wagon wheels and years of pigeon droppings and painted, wired, hammered, and nailed together the new home of the Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre, now in its 52nd year of performing Broadway musicals. Local Actors Martha Wright and Roland Chambers opened the theatre with I Do! I Do!, Camelot, 1776, Music Man, Cabaret, My Fair Lady, Auntie Mame, and all the great Broadway shows; three each summer adorn the stage of the ASGT under the stars.

brbrAlong West Street, professional theaters Compass Rose Theater and the Annapolis Shakespeare Company are newcomers to the Annapolis scene. They, too, offer award-winning drama productions. A performing arts center at Park Place, Maryland Theatre for the Performing Arts, was first recommended in 1980 by a commission established by Governor Harry Hughes, and is raising money for a new building to house productions in collaboration with Washington and Baltimore theater groups. Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts continues to sell out performances for the Annapolis Opera, Live Arts Maryland, and the Symphony, in its 900-seat refurbished old Annapolis High School home.

brbrTheater created a thriving, cultural fun and social city in the 1750s. It never went away, but theater life in the Annapolis took a sabbatical for a while. Our mentor, Athens, Greece, has 148 stages, the most of any city in the world. With a population of 700,600 that is about 4,727 people for each stage. Annapolis, with a population of 38,000, has eight stages if you include St. Johns College and the Naval Academy, each of which also produces stage shows. That is about 4,750 people per stage site—not bad for a small town. As for our other mentor, Bath, an architecturally significant spa city of festivals, Annapolis can match it, too. Theater, with its wit and learning that stirs our senses and the fun and laughter it brings with it, is once again alive and well in Maryland’s Capital City.

The Colonial Players

The Colonial Players

The Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre

Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts

Compass Rose Theatre

Annapolis Shakespeare Theater

St John’s College, King William Players

USNA Masqueraders

Children’s Theatre of Annapolis

Infinity Theatre

brbrCitizens in the New World named it “The Athens of America” and visitors proclaimed it “The Bath of America.” This was pretty high praise for a small town of 1,000 recently carved out of the wilderness in a new land on the Chesapeake Bay. Athens, being one of the world’s oldest cities after all, is acclaimed as the birthplace of western civilization and democracy and a center for the arts, learning, and philosophy. By 1784, the Annapolis had lived up to this tradition.

brbrBath, in England, was the most fashionable resort of the 18th century and the center of social elegance, with concerts, operas, and theater. In the Colonies, Annapolis was that resort. Bath, like Annapolis, is a city of Georgian architectural beauty. It is a World Heritage site that, today, hosts multiple international festivals for the arts. Local competitions for the best poet, singer, and storyteller awards include the “Bard of Bath.” In Colonial Annapolis, that award would have gone to Dr. Alexander Hamilton, founder in 1745 of the Tuesday Club. Dr. Upton Scott said of him “…he never failed to delight with the effusions of his wit, in which acquirements he had no equal…” Jonas Greene, the publisher of the Maryland Gazette, America’s first continuously published newspaper, might have been a good contender as well. Both were favorites of the ribaldry that occurred during the weekly meetings within the homes of the gentlemen of Annapolis, who were dedicated to wit and learning in the City’s first theater for the performing arts.

Laura Keene (1826–1873) was an Anglo-American actress and manager, whose real name was Mary Frances Moss. She performed at the Opera House on Maryland Avenue in Annapolis prior to her death in the same year.

brbrTheater, however, found fertile ground in Annapolis. Below the Mason Dixon line, the customs of England prevailed. Annapolis, described as more English than the English, idolized the English gentry. Reverend Jonathan Boucher, in his Reminiscences said: “I hardly know a town in England so desirable to live in as Annapolis.” The most famous men in England wrote plays and performed in them to the enjoyment of the proud aristocracy. Theater companies were family affairs. In Annapolis, theater brought refinement to the frontier city described as the “genteelest town in North America.”

brbrThe popular musical, The Beggars Opera, opened the city to performance of professional actors on June 18th, 1752. Managed by Murray and Kean, one of the first professional acting companies in the New World, they stayed in Annapolis for some time, producing performances of Cato and Richard III.

brbrWithin the decade, Kean was followed by the Hallam Company, sometimes called the first fully-professional theater to perform in North America. In the early days of theater, companies were family oriented. Adam, the Hallam patriarch, had been a respected actor at Covent Gardens in London. Four of his five sons followed in the profession. The Hallam Company, though noted for their experience and ability, however, were not making headway on the London Stage. William, the manager, decided to take a risk in America and brought the entire company of 12 performers and three children to the Colonies. And here, they made it well. In 1760, the entire summer season of theater shows was performed in Annapolis by the Hallam Company featuring Mr. John Palmer, an actor who excelled in comedy, from the Drury Lane Theatre in London.

Scribble from “The history of the ancient and honorable Tuesday club: From the earliest ages down to this present year. Annapolis, ca 1755.” Part of the collection at the John Work Garrett Library of the Johns Hopkins University.

brbrAll theater ceased during the War for Independence. The Golden Age of Annapolis, the Bath of America, was over. The first-of-its-kind theater was torn down in 1818. Its corner stone saved, according to Elihu Riley, in The Ancient City, to be used a decade later, in a new Hallam Theatre. In 1829, the French Corps de Ballet opened the new 500-seat Hallam Theatre on Duke of Gloucester Street. Despite good musical programs featuring the work of Haydn, Father of the Symphony and Father of the String Quartet, the theatre struggled financially. In 1846, it was purchased by the new Presbyterian Congregation led by Dr. John Ridout and Arsene Girault, a professor at the Naval Academy. The theatre was changed to a space of worship. The Hallam Theatre, built in 1829 and still largely intact—with a cornerstone that included the town’s newspapers, the names of the building committee, and a copy of George Washington’s Will—is now and has been the First Presbyterian Church of Annapolis since July, 1847.

brbrThe next years were turbulent for the Annapolis and the nation as a whole. There was not much joy in America. After thirty years of dark nights, The Masons were the first to bring professional theater back to Annapolis. In 1873, a new Opera House opened on Maryland Avenue at the corner of Prince George Street. Nationally-known and popular performer Laura Keene packed the house. Vaudeville shows, Gilbert and Sullivan Operettas, and local amateur companies entertained Annapolitans.

brbrOn May 18, 1903, a reconstructed 18th century estate, the Woodward/Dulaney house on Main Street, became a 1,000-seat live theater. Once part of Mann’s Tavern and the elegant City Hotel, the theater’s architects used the wall panels, elegant 18th century interior elements, and the staircase that led to the second floor (that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson had walked on) in the refurbished new theater. The Evening Capital wrote, “No playhouse in America can outrival this one in history.” When the 300 lights went on “the effect was magic and the view most beautiful.” In 1918, it was all gone, burned down in a devastating fire. The Hillman Garage now occupies the site that once housed a magnificent home, tavern, and hotel with gardens and a stable for 50 horses—once familiar to the founders of our Nation and the most elegant theater in Maryland.

Caricature of Annapolis-based doctor Alexander Hamilton, founder of the Tuesday Club. Image found in the manuscript of “The history of the ancient and honorable Tuesday club: From the earliest ages down to this present year. Annapolis, ca 1755.” Housed at The John Work Garrett Library of The Johns Hopkins University.

brbrColonial Players, a volunteer theatrical group, is approaching 70 years of award-winning performances. Initiated by Becky Clatanoff, whose name would adorn a building at Anne Arundel Medical Center, the Players began in 1949 to celebrate the City’s 300th anniversary. The performance of The Male Animal was staged at the abandoned USO building, and later City Recreation Center, on St Mary’s Street. Needing a permanent home, the Players found it in an old stable and auto shop at 108 East Street.

brbrRecycling old buildings seems to be a habit of Annapolis theater managers. Also needing a permanent home (after opening in the garden of the closed Carvel Hall Hotel with the Musical Brigadoon), Joan Baldwin, a visionary and creative genius who loved the challenge of making new ideas work, latched on to the abandoned Shaw Blacksmith Shop, circa 1836, located in an industrial waterfront district dating to1696, on Compromise Street. With no money but a lot of energy, actors and friends cleaned out old wagon wheels and years of pigeon droppings and painted, wired, hammered, and nailed together the new home of the Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre, now in its 52nd year of performing Broadway musicals. Local Actors Martha Wright and Roland Chambers opened the theatre with I Do! I Do!, Camelot, 1776, Music Man, Cabaret, My Fair Lady, Auntie Mame, and all the great Broadway shows; three each summer adorn the stage of the ASGT under the stars.

brbrAlong West Street, professional theaters Compass Rose Theater and the Annapolis Shakespeare Company are newcomers to the Annapolis scene. They, too, offer award-winning drama productions. A performing arts center at Park Place, Maryland Theatre for the Performing Arts, was first recommended in 1980 by a commission established by Governor Harry Hughes, and is raising money for a new building to house productions in collaboration with Washington and Baltimore theater groups. Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts continues to sell out performances for the Annapolis Opera, Live Arts Maryland, and the Symphony, in its 900-seat refurbished old Annapolis High School home.

First Presbyterian Church, on Duke of Gloucester Street in Annapolis, was originally The Hallam Theatre, built in 1829.

All historic images are within the public domain.

Active Annapolis Theater Companies

The Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre

Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts

Compass Rose Theatre

Annapolis Shakespeare Theater

St John’s College, King William Players

USNA Masqueraders

Children’s Theatre of Annapolis

Infinity Theatre