×

If you’ve called the City of Annapolis home for the better part of your life, you’ve experienced the myriad changes that have molded this historic metropolis into the vibrant state capital it is today. The balance between historic preservation of a city that dates back to the late-1600s and the contemporary wants and needs of its, now 40,000, population has been an ongoing challenge that spans decades, centuries. This probably holds true for most any city that embraces its history as much as its future. Funny thing about the time; the more distant we evolve from the past, the more we seem to long for it; a pining for the way things were seems an omnipresent sentiment, even when we have an eye on the future.

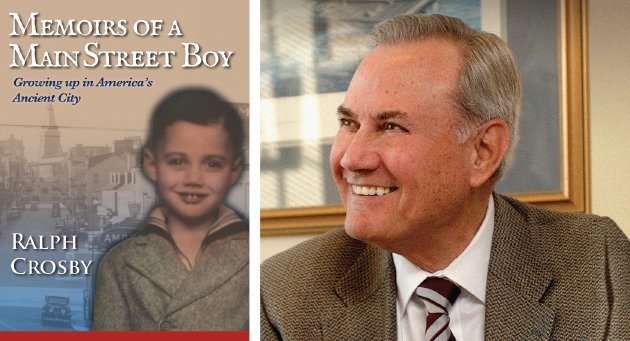

brbrIf you’re feeling nostalgic this holiday season, you’re not alone. Which is why we present excerpts from the recently published book Memoirs of a Main Street Boy written by Ralph W. Crosby, himself a lifelong Annapolitan, who shares his anecdotes of growing up “at a tempestuous time in U.S. history—from the Great Depression, through World War II and brthe Cold War.”

brbrAs tempestuous as those eras may have been on a grand scale, you’ll read plenty of feel-good memories of Annapolis in the 1930s and ’40s in the first two chapters of the book (verbatim), brwhich we present as follows.

brbr“Annapolitan” seems redolent of “Cosmopolitan” and sounds a bit pretentious for those who live in such a small town. Cosmopolitan or “cultured” might have fit Annapolis in the 18th Century, but certainly not in the 20th. It’s also hard to give undue importance to a boy growing up on Main Street, the two-and-a-half block commercial center of Annapolis, especially a youngster living in a third floor, walk-up apartment during what were, to paraphrase Charles Dickens, “the best of times, the worst of times.”

brbrThe worst of times because I was born in the latter part of the “Great Depression,” December 16, 1933, to be exact, and spent a youth punctuated by wars – the Second World War, the Cold War and the Korean War.

brbrThe best of times – being a youngster in a town surrounded by fish-and-crab-filled creeks and rivers snaking off the Chesapeake Bay, where you could walk to those waters to swim and fish, walk to school, walk to the library or to the ball fields and gymnasiums of St. John’s College and the United States Naval Academy. I walked to them all.

brbrWhen I was four years old, my mom, dad and I moved to the third floor apartment brat 183 Main Street, where I would live for the next 20 years.

brbrAs a young child, that apartment seemed like a huge place. Only when I reached my teen years, having experienced the larger homes of some friends, did I realize how small it was. But through all the years, it had the sweet experience, then memories, of “home” and all that word means to those who love family and neighborhood.

brbr“Neighborhood” had a lot to do with the experience, because mine was rich in brsmall town closeness and the magic of colonial American history rivaled only by Boston and Philadelphia.

brbrThe apartment at 183 Main Street was like so many others of the day, situated above the stores on the main business street.

brbr“Main Street,” of course, has taken on special significance in the U.S., a generic representation of all small town central retail streets, even representing small business people as opposed to “Wall Street” as representative of big business. Like those in other small towns, my Main Street reflected the street life of the city, with holiday parades; Saturday night walkers, drinkers and shoppers; auto-owner showoffs; movie goers; and Sunday church goers. Being raised at 183 Main Street put me at the epicenter of small town life.

brbrYou entered 183 from a door-wide set of three steps located between a dress shop and a stationery store. Climbing two long dark flights of stairs, you entered the apartment into a long hall with several rooms off it, including the “front room,” or living room. The front room, of course, faced Main Street, and through its large windows I could watch my small world go by and imagine some of the greatest events of the American Revolution that unfolded nearby.

brbrLiving on Main Street made you somewhat immune to sounds – such as car horns blasting each other, except for the older cars, whose distinguishing horns emitted an “ooga, ooga” rather than the more shrill bugle call. In summer, with screens in the windows, even conversations wafted up to the third floor, and there were always kids yelling as they played. The sound that penetrated was the siren of a fire truck from the station on nearby Duke of Gloucester Street as it sped through the downtown. It’s remarkable how these trucks could maneuver through narrow streets built for horse and buggy travel.

brbrThe front room had a sofa, two stuffed chairs and an upright radio console, with a rug on the floor where I would lay listening to Sammy Baugh lead the Washington Redskins into a pro football battle or the Lone Ranger, riding “the great horse Silver,” with his Indian companion Tonto at his side, routing another bunch of bad guys. The radio had buttons you pushed to select a station. It even had one labeled “television,” though we had no idea what that was.

brbrThe apartment consisted of five other rooms, two bedrooms, a dining room, a tiny bathroom and a not-much-bigger kitchen. There was a pantry off the kitchen housing a refrigerator and shelves for canned goods and other foodstuffs. With a stove, a sink, a table that could fit the three of us – for I was an only child – and a hot water heater and radiator, you could only move through the kitchen one person at a time.

brbrThe hot water heater or boiler had to be lit every time you wanted to take a bath. You also had to be sure to turn off the gas so the boiler wouldn’t get too hot and explode. In the bathroom, there was only a tub – no shower. I didn’t know what a shower was until around age nine when I started playing basketball in the high school gym.

brbrThe bathroom was so tiny that by the time my mother got her first washing machine, you had to pull in your stomach to get to the sink or toilet. Of course, in my younger days I remember my mother hunched over the bathtub washing clothes on a scrub board. When she did get a washing machine, it had to be hooked up to the spigots on the sink and had a wringer that you hand fed your washed clothing to press out the water – at the risk of crushed fingers.

brbrOff the kitchen were the back stairs and the entrance to my favorite place as a child – the back porch. Only about 12 feet by 20 feet, it was a place of learning and a place of fantasy. It even supplied Seckel pears from the tree in the yard next door, which I could reach with my long-handled crab net. The fact that the yard next door was the side yard of an historic 18th century home was lost on me until many years later.

brbrSo, that apartment was my everyday home until I went off to college at 18 and my brback-from-school home until I was 24 and got married.

brbrOne-third of the way from the top of the street, the apartment’s two large front windows presented a special view of my world. If you leaned out one of the windows, with your knees on the floor, you could survey all of Main Street and even see above the buildings across the street and glimpse some of Annapolis’ historic highlights.

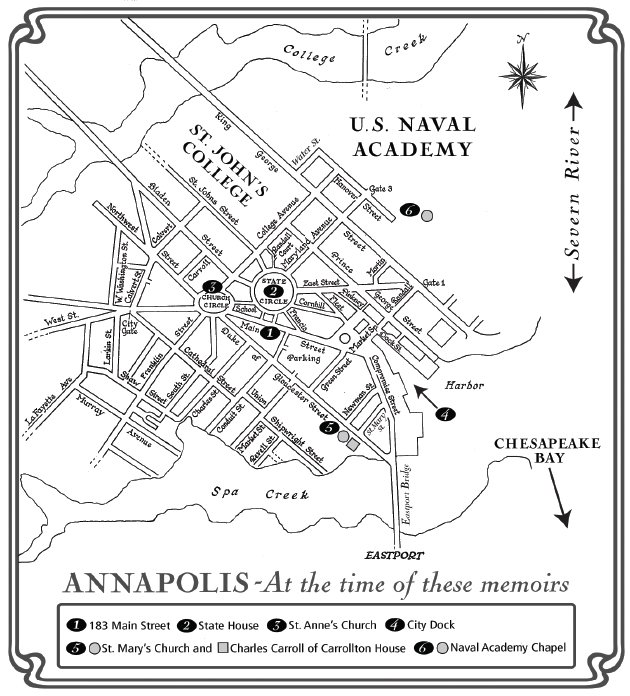

brbrJust a seven to eight minute stroll from top to bottom, Main Street is bounded at the top by the round-about road called Church Circle, dominated in its center by historic St. Anne’s Episcopal Church, and at its bottom by the venerable city dock, structured remains of the harbor that originally defined the city.

brbrIn the early 1700s, Main Street was a block shorter than in my day because the “dock,” originally a synonym for harbor, extended haphazardly higher into the city. But the brlink of this maritime economic engine of the area with the power base of the colonies, represented by the Protestant St. Anne’s Church, gave Main Street significance beyond Annapolis.

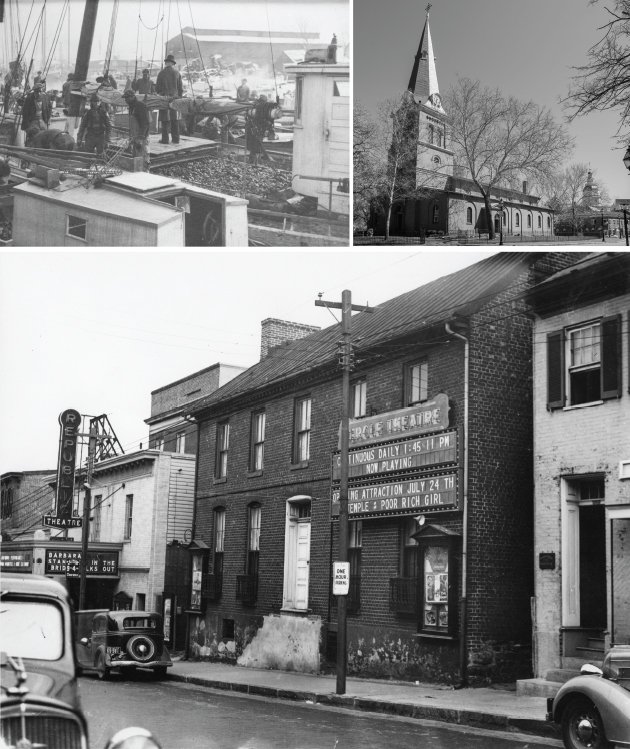

brbrOur apartment was on the left side of the street going up, so that if I looked out the front window two blocks to the right would be the city dock with its waterman’s workboats, an occasional pleasure craft and, in the background, where the Chesapeake Bay fed into the Severn River, dots of white and grey as sailboats frolicked and workboats plied their trade, fishing, crabbing and oystering the bountiful waters. Sometimes, the dock was so filled with skipjacks and other workboats, you could walk across its narrow head – some 50 to 60 feet wide – using boats secured side-by-side as stepping stones.

brbrThe landing side of the dock, shrunk considerably from its colonial port size, in my youth and now, mimics the size of a football field, spreading out somewhat in length and width as it exits into the river. (See map)

brbrSailing out of the dock and tacking starboard, you enter Spa Creek which, in my youth, was the eastern boundary of the city. On the Creek, you sail past the manor house of Charles Carrol of Carrollton, one of the most venerated signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, and brinto the waters of my boyhood adventures and misadventures.

brbrIf you sail out of the dock to the port side, you’ll be at the seawall of the U.S. Naval Academy, which hugs the broad, Severn River, bounded landside by parade grounds and sports fields, for midshipmen marching and ball-playing and playgrounds for me and my young pals.

brbrFrom my window, on a clear day, as you look past the harbor, you could see across the Bay to the outline of the Eastern Shore of Maryland, some four or five miles away. Leaning out the window, if you panned from the Bay over the city you’d see several of the hallmark spires that rose over Annapolis, beacons of American history.

brbrGreenbury Point, often referred to aptly as “North Severn,” was home to the Navy’s Engineering Experiment Station that tested Naval equipment, from the first biplane to modern jet engines. The towers, which dominated the skyline entering the Bay, were erected in 1918 to support a high powered radio station as a First World War precaution to keep communications open with Europe if the enemy cut undersea cables. The communications capacity at North Severn was greatly expanded in World War II to become the primary transmitting station to Navy ships deployed around the world.

brbrThe towers were landmarks for Bay watermen since they could be seen from miles away, and for my father, who saw them being erected, they meant home whenever he returned from trips out of town, which were few and far between. Many times, I heard him say, “I never want to get so far away from Annapolis that I can’t see the radio towers.”

brbrGreenbury Point was also the place where the Puritans, Virginia immigrants who would create Annapolis, first settled in the 1649-1650 timeframe before moving to the south side of the Severn River. (The more purist local historians don’t like using “Puritans” to describe these immigrants who settled along the Severn. The Puritans were only one brand of English dissenters, discontented with the Church of England, who escaped persecution from brchurch leaders and the King by immigrating to America. With that understood, I’ll use “Puritan” as the simplest descriptor for these Severn area settlers.)

brbrPanning farther left, you’d see the top of the copper dome of the Naval Academy Chapel, weathered to a green patina, and directly over the buildings across from 183 Main Street would rise the majestic wooden dome of the Maryland State House, one of the nation’s most historic buildings. (I’ll have more to say later about these two basilicas.) Then, looking to the left up Main Street, the gothic steeple of St. Anne’s acted as an arrow pointing skyward from the center of the City.

brbrIn size and appearance, the church is not cathedral-like. In fact, it is small by most standards. But it is a stately, brick structure that rises about three stories high, at least a floor higher than its neighbors in my youth. Its steeple can be seen from blocks away and the tower holds four town clocks one each facing the four main points of the compass.

brbrWhile knowing the time of day, especially since the church bells rang on the quarter hour, was convenient for most, these clocks took away my boyhood lateness excuse, “I didn’t know what time it was.” Though I didn’t own a watch, my mother knew I was playing seldom more than a few blocks from Church Circle and easily could have checked the clocks.

brbrFrom Church Circle, lining both sides of Main Street to the dock, the shops and civic establishments supplied almost everything a family needed to live.

brbrWhere Church Circle first meets Main Street, on the 183 side, stands the Maryland Inn, built in 1782, lodging and feeding guests, especially legislators, then and now. In my day, across the street opposite the Inn was Annapolis Banking and Trust Company, a local institution where my mother spent a short while as a teller in one of her many jobs and where, as an adult, I would serve on its Board of Directors for a long while, 26 years, before it was sold to a larger bank.

brbrIf you scanned Main Street from top to bottom, the store signs hung out over the sidewalks like colorful flags of different shapes vying for attention among the electric poles and utility lines that crisscrossed the street. To be honest, the poles and lines spoiled the view to the dock or St. Anne’s; they were distractions, like food stains on a clean, white shirt. In those days, I would have agreed with one of Sinclair Lewis’ characters in his novel Main Street: “I do admit that Main Street is not as beautiful as it should be.” (Thankfully, by the mid-1990s the signs over sidewalks were legislated away and the utility lines went underground, making Main Street much more beautiful than in my youth.)

brbrThe store signs shouted “Shoe Store;” “Men’s-Ladies Wear;” “Public Loan Office” emblazoned with its pawn shop balls; “Furniture,” “Rexall Drugs;” and restaurant names galore.

brbrMain Street restaurants became personal havens over the years. I played chess with the proprietor in a tiny eatery called The New Grill; put too many nickels in the pinball machines in the Wardroom Restaurant; kept a few nickels for late evening ten-cents-a-piece hamburgers brat the Little Tavern; took my earliest dates for pizza at LaRosa’s; and met my high school chums after school at the dining area at the rear of Read’s Drug Store.

brbrMain Street boasted not one but two five and ten cent stores, Murphy’s at the foot of Main Street and Woolworth’s, a bit up and across from 183. What I remember most about both were the open displays of candy inside their doors, and I must admit to some sticky fingers as I passed these enticing rows of sweets, especially coveting one of my favorites, a Mary Jane or a Bit-O-Honey.

brbrJust up the street from Woolworth’s was the Maggio family’s fruit and vegetable store, with the grandiose name “Annapolis Fruit and Produce Company,” where I cleaned up and stocked food for one summer as a youngster. The tiny store, run by two older immigrants from Italy and overseen by their entrepreneurial son, Tony, was distinguished by the peanut roasting machine that stood out front on the sidewalk. A bulky, metal machine that used a strip heater to roast the peanuts, it produced warm nuts in their shells that had a distinct taste I haven’t experienced since.

brbrBeyond Maggio’s was a doorway with white columns with the letters above it proclaiming B.P.O.E. We would joke that stood for “Best People On Earth,” rather than “Benevolent Protective Order of Elks.” The joke satisfied me since my dad was a member and, through the years, it became an entertainment center for me, as well – from a place to watch football bron television, since we didn’t own a set until my late teens, to the sponsor of my one summer camp in the mountains of Western Maryland, to dances with my mother when I’d stop in the Elks on Saturday night in my late teens.

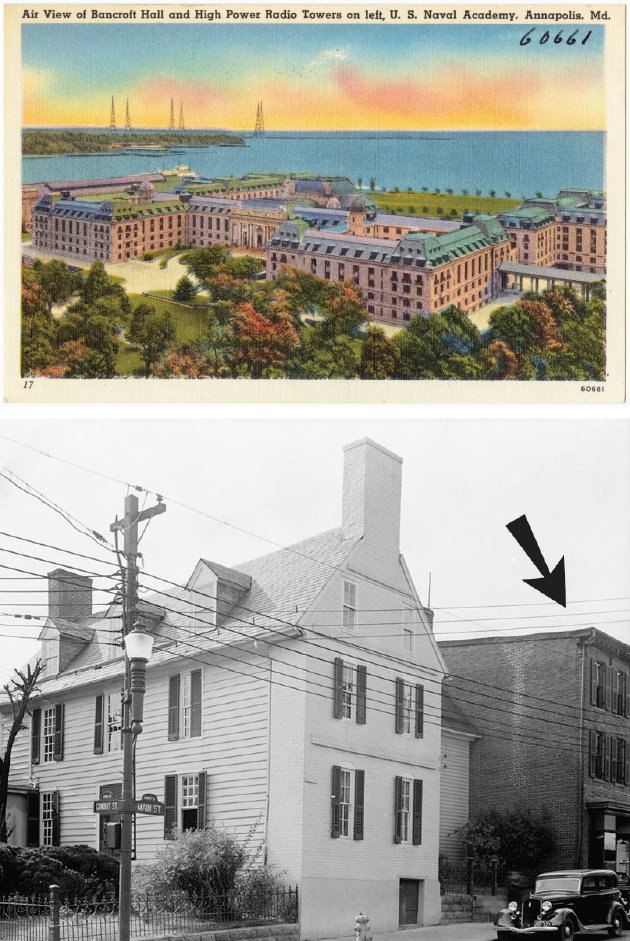

brbrMy biggest formal entertainment spot was one building up from our apartment – the Republic Movie Theater, another place where both my mother and I worked for short stints – she as a ticket seller and I as an usher. And the movie house had a parking lot next door, where we played ball and ate grapes off the fence in the rear of the lot. Grapes in a parking lot, pears, apples or cherries for picking on nearby neighborhood trees – all seemed quite natural in those days in Annapolis. The “movie lot,” as we called it, sat next to the massive concrete wall of the theater. I used that wall as a backboard to play catch with myself with a lacrosse ball and stick, lacrosse being a traditional Maryland sport that I would play in high school and college.

brbrThere were at least three grocery stores on Main Street, plus a meat market, a bakery, jewelers, stationers, gift shops, hat stores, several pharmacies, and the offices and sales floor of the Gas and Electric Company.

brbrWe even had an Amoco gas station at the foot of Main Street in the middle of the traffic circle adjacent to the city dock.

brbrSome buildings had signs painted on their sides, such as “Genuine Bull Durham Tobacco” for roll-your-own cigarettes or “Credit” on the furniture store wall. Many had awnings out front that could be cranked open to shield patrons from the rain or sun. Those awnings, red, green, blue or striped, made Main Street more colorful, if not beautiful.

brbrMost of these first-floor stores were topped with one or two floors of living space, like 183, the general plan for apartment living for working-class Annapolitans.

brbrThose windows of 183 witnessed many an event both monumental and simply personal. For example, it was those windows, covered by dark shades to keep from revealing light that theoretically might attract bombers in World War II, which were thrown open to hear the sounds of paper boys shouting “Extra. Extra. The War is over” in 1945. On the more trivial and personal level, it was through those windows that my mother watched me cross the street to the grocery store and emerge with a candy bar that she knew I had no money to pay for. I was six or seven and received a lesson in honesty and apology as well as a sore behind.

brbrLooking down to the right, I might see my friends gathered on the stone steps of the house next door. Those three broad, stone steps were our “street corner,” where we’d guess the makes of cars going up Main Street or debate the baseball greatness of Ted Williams versus Joe DiMaggio.

brbrOf course, like many things in Annapolis, those stone steps had historic significance. They led to the side entrance of what was known in colonial times as the Carroll Barrister House, built in the early 1720s and home of the patriot Charles Carroll the Barrister, who was born there in 1724.

brbrCarroll the Barrister fought the infamous stamp and tea taxes, led a boycott of British goods, served in the Continental Congress and was the principal writer of the Declaration of Delegates of Maryland, at the same time with the same purpose as our Declaration of Independence.

brbrThe house, itself, one of the great surviving examples of 18th Century architecture, not only gave me and my pals a stoop for gathering, but its yard supplied me with those tasty Seckel pears from its ancient tree. My mother watched from our front windows in 1955 when the old house was torn from its foundation and carted up Main Street to its current home on the St. Johns College campus. It soon would be replaced by, of all things, a Burger King.

brbrOn any weekday shortly after 5 p.m., I could look out the window to see my dad walking home from his job as a sheet metal worker at the Naval Academy and see him stop at the pool room on Main Street for his perennial ten-cent glass of beer before heading home for dinner.

brbrI could also watch midshipmen marching from the Naval Academy, whether it was on Sunday to church or celebrating a football win over Army. The street cleared as the blue-suited, white-capped brigade members moved in perfect unison to the “Hut, One, Two, Three, Hut” call. Among them could have been future President James Earl Carter (Class of 1946); Astronaut Alan Shepard (Class of 1944), the first American to travel in space; Walter (Wally) Schirra, Jr. (Class of 1945), along with Shepard, one of the original seven Mercury Astronauts, and the one I would interview as a young newspaper reporter right after he was chosen as an astronaut.

brbrMarching by my window would be numerous future Naval heroes who would fight our wars, and also sports heroes, several of whom, later in life, became my friends – as would several who were later imprisoned during the Vietnam War. Annapolis, the city, had a way of getting into the hearts of many midshipmen, and they returned to our town to live, especially in retirement.

brbrEarlier, in 1781, I could have seen the Marquis de Lafayette and his lieutenants entering a Church Street hostelry to dine after leaving their American troops bivouacked across Spa Creek from Annapolis.

brbrEven earlier, in 1774, in a popular inn on upper Church Street called the “Coffee House,” you might have encountered, on his way to Williamsburg, one Patrick Henry, a Virginia assemblyman held high in esteem by all those who sought independence from Great Britain.

brbrIt was Henry, who on March 23, 1775, would speak those words that would stir his compatriots then and stir most of us as far back as Grammar school:

brbr“Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!”

brbrWith such a time machine, I could jump forward to 1789 and watch the 10-year-old Francis Scott Key cross Church Street on his way to King Williams School, which would become St. John’s College, from which Key would graduate as one of its accomplished academics and amateur poets and a soon-to-be lawyer. This same young man would find himself in 1814 watching “bombs bursting in air that gave proof through the night that our flag was still there” on a ship off Baltimore’s Fort McHenry.

brbrMore personally, I could see back to around 1730 and watch my great-great-great-great-great grandfather Burden Crosby, Commander of “The George,” bring his ship into the Annapolis harbor, picking up tobacco to transport to London.

brbrOur mythical time machine could also show ancient sights you might not like to see. Besides ships that brought some of the nation’s founders to Annapolis and ones that carried tobacco to England returning with all types of goods, you would see ships of agony docking in Annapolis harbor – slave ships that brought to America chained, sickened Africans such as famed author Alex Haley’s ancestor, Kunta Kinte, immortalized in Haley’s book Roots.

brbrOne of the most inspirational scenes we could view through our window time machine would be that of a large white horse carrying a tall man, with powdered hair and militarily dress with a cape over his shoulder to fend off the December 23, 1783 chill, leaving a Church Street hotel for the State House. The man was George Washington, on his way to take the momentous action of resigning his commission as Commander In Chief of the Continental Army, a decision described by one biographer, and echoed by many, as “the most significant address ever delivered to a civil society.”

brbrIf you’re feeling nostalgic this holiday season, you’re not alone. Which is why we present excerpts from the recently published book Memoirs of a Main Street Boy written by Ralph W. Crosby, himself a lifelong Annapolitan, who shares his anecdotes of growing up “at a tempestuous time in U.S. history—from the Great Depression, through World War II and brthe Cold War.”

brbrAs tempestuous as those eras may have been on a grand scale, you’ll read plenty of feel-good memories of Annapolis in the 1930s and ’40s in the first two chapters of the book (verbatim), brwhich we present as follows.

Chapter One

Viewing The World From A Third Floor Apartment

brbrI’m what is called an “Annapolitan” – born, raised and always with a home in Annapolis, Maryland.brbr“Annapolitan” seems redolent of “Cosmopolitan” and sounds a bit pretentious for those who live in such a small town. Cosmopolitan or “cultured” might have fit Annapolis in the 18th Century, but certainly not in the 20th. It’s also hard to give undue importance to a boy growing up on Main Street, the two-and-a-half block commercial center of Annapolis, especially a youngster living in a third floor, walk-up apartment during what were, to paraphrase Charles Dickens, “the best of times, the worst of times.”

brbrThe worst of times because I was born in the latter part of the “Great Depression,” December 16, 1933, to be exact, and spent a youth punctuated by wars – the Second World War, the Cold War and the Korean War.

brbrThe best of times – being a youngster in a town surrounded by fish-and-crab-filled creeks and rivers snaking off the Chesapeake Bay, where you could walk to those waters to swim and fish, walk to school, walk to the library or to the ball fields and gymnasiums of St. John’s College and the United States Naval Academy. I walked to them all.

brbrWhen I was four years old, my mom, dad and I moved to the third floor apartment brat 183 Main Street, where I would live for the next 20 years.

brbrAs a young child, that apartment seemed like a huge place. Only when I reached my teen years, having experienced the larger homes of some friends, did I realize how small it was. But through all the years, it had the sweet experience, then memories, of “home” and all that word means to those who love family and neighborhood.

brbr“Neighborhood” had a lot to do with the experience, because mine was rich in brsmall town closeness and the magic of colonial American history rivaled only by Boston and Philadelphia.

brbrThe apartment at 183 Main Street was like so many others of the day, situated above the stores on the main business street.

brbr“Main Street,” of course, has taken on special significance in the U.S., a generic representation of all small town central retail streets, even representing small business people as opposed to “Wall Street” as representative of big business. Like those in other small towns, my Main Street reflected the street life of the city, with holiday parades; Saturday night walkers, drinkers and shoppers; auto-owner showoffs; movie goers; and Sunday church goers. Being raised at 183 Main Street put me at the epicenter of small town life.

brbrYou entered 183 from a door-wide set of three steps located between a dress shop and a stationery store. Climbing two long dark flights of stairs, you entered the apartment into a long hall with several rooms off it, including the “front room,” or living room. The front room, of course, faced Main Street, and through its large windows I could watch my small world go by and imagine some of the greatest events of the American Revolution that unfolded nearby.

brbrLiving on Main Street made you somewhat immune to sounds – such as car horns blasting each other, except for the older cars, whose distinguishing horns emitted an “ooga, ooga” rather than the more shrill bugle call. In summer, with screens in the windows, even conversations wafted up to the third floor, and there were always kids yelling as they played. The sound that penetrated was the siren of a fire truck from the station on nearby Duke of Gloucester Street as it sped through the downtown. It’s remarkable how these trucks could maneuver through narrow streets built for horse and buggy travel.

brbrThe front room had a sofa, two stuffed chairs and an upright radio console, with a rug on the floor where I would lay listening to Sammy Baugh lead the Washington Redskins into a pro football battle or the Lone Ranger, riding “the great horse Silver,” with his Indian companion Tonto at his side, routing another bunch of bad guys. The radio had buttons you pushed to select a station. It even had one labeled “television,” though we had no idea what that was.

brbrThe apartment consisted of five other rooms, two bedrooms, a dining room, a tiny bathroom and a not-much-bigger kitchen. There was a pantry off the kitchen housing a refrigerator and shelves for canned goods and other foodstuffs. With a stove, a sink, a table that could fit the three of us – for I was an only child – and a hot water heater and radiator, you could only move through the kitchen one person at a time.

brbrThe hot water heater or boiler had to be lit every time you wanted to take a bath. You also had to be sure to turn off the gas so the boiler wouldn’t get too hot and explode. In the bathroom, there was only a tub – no shower. I didn’t know what a shower was until around age nine when I started playing basketball in the high school gym.

brbrThe bathroom was so tiny that by the time my mother got her first washing machine, you had to pull in your stomach to get to the sink or toilet. Of course, in my younger days I remember my mother hunched over the bathtub washing clothes on a scrub board. When she did get a washing machine, it had to be hooked up to the spigots on the sink and had a wringer that you hand fed your washed clothing to press out the water – at the risk of crushed fingers.

brbrOff the kitchen were the back stairs and the entrance to my favorite place as a child – the back porch. Only about 12 feet by 20 feet, it was a place of learning and a place of fantasy. It even supplied Seckel pears from the tree in the yard next door, which I could reach with my long-handled crab net. The fact that the yard next door was the side yard of an historic 18th century home was lost on me until many years later.

brbrSo, that apartment was my everyday home until I went off to college at 18 and my brback-from-school home until I was 24 and got married.

brbrOne-third of the way from the top of the street, the apartment’s two large front windows presented a special view of my world. If you leaned out one of the windows, with your knees on the floor, you could survey all of Main Street and even see above the buildings across the street and glimpse some of Annapolis’ historic highlights.

brbrJust a seven to eight minute stroll from top to bottom, Main Street is bounded at the top by the round-about road called Church Circle, dominated in its center by historic St. Anne’s Episcopal Church, and at its bottom by the venerable city dock, structured remains of the harbor that originally defined the city.

brbrIn the early 1700s, Main Street was a block shorter than in my day because the “dock,” originally a synonym for harbor, extended haphazardly higher into the city. But the brlink of this maritime economic engine of the area with the power base of the colonies, represented by the Protestant St. Anne’s Church, gave Main Street significance beyond Annapolis.

brbrOur apartment was on the left side of the street going up, so that if I looked out the front window two blocks to the right would be the city dock with its waterman’s workboats, an occasional pleasure craft and, in the background, where the Chesapeake Bay fed into the Severn River, dots of white and grey as sailboats frolicked and workboats plied their trade, fishing, crabbing and oystering the bountiful waters. Sometimes, the dock was so filled with skipjacks and other workboats, you could walk across its narrow head – some 50 to 60 feet wide – using boats secured side-by-side as stepping stones.

brbrThe landing side of the dock, shrunk considerably from its colonial port size, in my youth and now, mimics the size of a football field, spreading out somewhat in length and width as it exits into the river. (See map)

brbrSailing out of the dock and tacking starboard, you enter Spa Creek which, in my youth, was the eastern boundary of the city. On the Creek, you sail past the manor house of Charles Carrol of Carrollton, one of the most venerated signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, and brinto the waters of my boyhood adventures and misadventures.

brbrIf you sail out of the dock to the port side, you’ll be at the seawall of the U.S. Naval Academy, which hugs the broad, Severn River, bounded landside by parade grounds and sports fields, for midshipmen marching and ball-playing and playgrounds for me and my young pals.

brbrFrom my window, on a clear day, as you look past the harbor, you could see across the Bay to the outline of the Eastern Shore of Maryland, some four or five miles away. Leaning out the window, if you panned from the Bay over the city you’d see several of the hallmark spires that rose over Annapolis, beacons of American history.

Chapter Two

Beacons of History

brbrLooking dockward out my front window, the first spires to arise are the radio towers on Greenbury Point, the peninsula on the north side of the Severn River, where it meets the Bay, across from the Naval Academy.brbrGreenbury Point, often referred to aptly as “North Severn,” was home to the Navy’s Engineering Experiment Station that tested Naval equipment, from the first biplane to modern jet engines. The towers, which dominated the skyline entering the Bay, were erected in 1918 to support a high powered radio station as a First World War precaution to keep communications open with Europe if the enemy cut undersea cables. The communications capacity at North Severn was greatly expanded in World War II to become the primary transmitting station to Navy ships deployed around the world.

brbrThe towers were landmarks for Bay watermen since they could be seen from miles away, and for my father, who saw them being erected, they meant home whenever he returned from trips out of town, which were few and far between. Many times, I heard him say, “I never want to get so far away from Annapolis that I can’t see the radio towers.”

brbrGreenbury Point was also the place where the Puritans, Virginia immigrants who would create Annapolis, first settled in the 1649-1650 timeframe before moving to the south side of the Severn River. (The more purist local historians don’t like using “Puritans” to describe these immigrants who settled along the Severn. The Puritans were only one brand of English dissenters, discontented with the Church of England, who escaped persecution from brchurch leaders and the King by immigrating to America. With that understood, I’ll use “Puritan” as the simplest descriptor for these Severn area settlers.)

brbrPanning farther left, you’d see the top of the copper dome of the Naval Academy Chapel, weathered to a green patina, and directly over the buildings across from 183 Main Street would rise the majestic wooden dome of the Maryland State House, one of the nation’s most historic buildings. (I’ll have more to say later about these two basilicas.) Then, looking to the left up Main Street, the gothic steeple of St. Anne’s acted as an arrow pointing skyward from the center of the City.

brbrIn size and appearance, the church is not cathedral-like. In fact, it is small by most standards. But it is a stately, brick structure that rises about three stories high, at least a floor higher than its neighbors in my youth. Its steeple can be seen from blocks away and the tower holds four town clocks one each facing the four main points of the compass.

brbrWhile knowing the time of day, especially since the church bells rang on the quarter hour, was convenient for most, these clocks took away my boyhood lateness excuse, “I didn’t know what time it was.” Though I didn’t own a watch, my mother knew I was playing seldom more than a few blocks from Church Circle and easily could have checked the clocks.

brbrFrom Church Circle, lining both sides of Main Street to the dock, the shops and civic establishments supplied almost everything a family needed to live.

brbrWhere Church Circle first meets Main Street, on the 183 side, stands the Maryland Inn, built in 1782, lodging and feeding guests, especially legislators, then and now. In my day, across the street opposite the Inn was Annapolis Banking and Trust Company, a local institution where my mother spent a short while as a teller in one of her many jobs and where, as an adult, I would serve on its Board of Directors for a long while, 26 years, before it was sold to a larger bank.

brbrIf you scanned Main Street from top to bottom, the store signs hung out over the sidewalks like colorful flags of different shapes vying for attention among the electric poles and utility lines that crisscrossed the street. To be honest, the poles and lines spoiled the view to the dock or St. Anne’s; they were distractions, like food stains on a clean, white shirt. In those days, I would have agreed with one of Sinclair Lewis’ characters in his novel Main Street: “I do admit that Main Street is not as beautiful as it should be.” (Thankfully, by the mid-1990s the signs over sidewalks were legislated away and the utility lines went underground, making Main Street much more beautiful than in my youth.)

brbrThe store signs shouted “Shoe Store;” “Men’s-Ladies Wear;” “Public Loan Office” emblazoned with its pawn shop balls; “Furniture,” “Rexall Drugs;” and restaurant names galore.

brbrMain Street restaurants became personal havens over the years. I played chess with the proprietor in a tiny eatery called The New Grill; put too many nickels in the pinball machines in the Wardroom Restaurant; kept a few nickels for late evening ten-cents-a-piece hamburgers brat the Little Tavern; took my earliest dates for pizza at LaRosa’s; and met my high school chums after school at the dining area at the rear of Read’s Drug Store.

brbrMain Street boasted not one but two five and ten cent stores, Murphy’s at the foot of Main Street and Woolworth’s, a bit up and across from 183. What I remember most about both were the open displays of candy inside their doors, and I must admit to some sticky fingers as I passed these enticing rows of sweets, especially coveting one of my favorites, a Mary Jane or a Bit-O-Honey.

brbrJust up the street from Woolworth’s was the Maggio family’s fruit and vegetable store, with the grandiose name “Annapolis Fruit and Produce Company,” where I cleaned up and stocked food for one summer as a youngster. The tiny store, run by two older immigrants from Italy and overseen by their entrepreneurial son, Tony, was distinguished by the peanut roasting machine that stood out front on the sidewalk. A bulky, metal machine that used a strip heater to roast the peanuts, it produced warm nuts in their shells that had a distinct taste I haven’t experienced since.

brbrBeyond Maggio’s was a doorway with white columns with the letters above it proclaiming B.P.O.E. We would joke that stood for “Best People On Earth,” rather than “Benevolent Protective Order of Elks.” The joke satisfied me since my dad was a member and, through the years, it became an entertainment center for me, as well – from a place to watch football bron television, since we didn’t own a set until my late teens, to the sponsor of my one summer camp in the mountains of Western Maryland, to dances with my mother when I’d stop in the Elks on Saturday night in my late teens.

brbrMy biggest formal entertainment spot was one building up from our apartment – the Republic Movie Theater, another place where both my mother and I worked for short stints – she as a ticket seller and I as an usher. And the movie house had a parking lot next door, where we played ball and ate grapes off the fence in the rear of the lot. Grapes in a parking lot, pears, apples or cherries for picking on nearby neighborhood trees – all seemed quite natural in those days in Annapolis. The “movie lot,” as we called it, sat next to the massive concrete wall of the theater. I used that wall as a backboard to play catch with myself with a lacrosse ball and stick, lacrosse being a traditional Maryland sport that I would play in high school and college.

brbrThere were at least three grocery stores on Main Street, plus a meat market, a bakery, jewelers, stationers, gift shops, hat stores, several pharmacies, and the offices and sales floor of the Gas and Electric Company.

brbrWe even had an Amoco gas station at the foot of Main Street in the middle of the traffic circle adjacent to the city dock.

brbrSome buildings had signs painted on their sides, such as “Genuine Bull Durham Tobacco” for roll-your-own cigarettes or “Credit” on the furniture store wall. Many had awnings out front that could be cranked open to shield patrons from the rain or sun. Those awnings, red, green, blue or striped, made Main Street more colorful, if not beautiful.

brbrMost of these first-floor stores were topped with one or two floors of living space, like 183, the general plan for apartment living for working-class Annapolitans.

brbrThose windows of 183 witnessed many an event both monumental and simply personal. For example, it was those windows, covered by dark shades to keep from revealing light that theoretically might attract bombers in World War II, which were thrown open to hear the sounds of paper boys shouting “Extra. Extra. The War is over” in 1945. On the more trivial and personal level, it was through those windows that my mother watched me cross the street to the grocery store and emerge with a candy bar that she knew I had no money to pay for. I was six or seven and received a lesson in honesty and apology as well as a sore behind.

brbrOf course, like many things in Annapolis, those stone steps had historic significance. They led to the side entrance of what was known in colonial times as the Carroll Barrister House, built in the early 1720s and home of the patriot Charles Carroll the Barrister, who was born there in 1724.

brbrCarroll the Barrister fought the infamous stamp and tea taxes, led a boycott of British goods, served in the Continental Congress and was the principal writer of the Declaration of Delegates of Maryland, at the same time with the same purpose as our Declaration of Independence.

brbrThe house, itself, one of the great surviving examples of 18th Century architecture, not only gave me and my pals a stoop for gathering, but its yard supplied me with those tasty Seckel pears from its ancient tree. My mother watched from our front windows in 1955 when the old house was torn from its foundation and carted up Main Street to its current home on the St. Johns College campus. It soon would be replaced by, of all things, a Burger King.

brbrOn any weekday shortly after 5 p.m., I could look out the window to see my dad walking home from his job as a sheet metal worker at the Naval Academy and see him stop at the pool room on Main Street for his perennial ten-cent glass of beer before heading home for dinner.

brbrI could also watch midshipmen marching from the Naval Academy, whether it was on Sunday to church or celebrating a football win over Army. The street cleared as the blue-suited, white-capped brigade members moved in perfect unison to the “Hut, One, Two, Three, Hut” call. Among them could have been future President James Earl Carter (Class of 1946); Astronaut Alan Shepard (Class of 1944), the first American to travel in space; Walter (Wally) Schirra, Jr. (Class of 1945), along with Shepard, one of the original seven Mercury Astronauts, and the one I would interview as a young newspaper reporter right after he was chosen as an astronaut.

brbrMarching by my window would be numerous future Naval heroes who would fight our wars, and also sports heroes, several of whom, later in life, became my friends – as would several who were later imprisoned during the Vietnam War. Annapolis, the city, had a way of getting into the hearts of many midshipmen, and they returned to our town to live, especially in retirement.

Back in Time

brbrNow, suppose my living room window had been a time machine, able to take me back to Annapolis in the 1700s. I might have seen the Sons of Liberty, a group of distinguished patriots, leaving a Church Street hostelry for the State House, preparing to declare independence from Great Britain, fight a revolutionary war, and write a Declaration of Independence and a constitution. Or I might look up toward Church Circle in 1784 and see members of the Continental Congress walking from the State House to the Maryland Inn for a celebratory drink after ratifying the Treaty of Paris, the treaty that officially ended the war for independence. Around 1784, I also might have seen two future presidents, Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe, leaving their rented house near Church Circle to do business on Main Street (then called Church Street).brbrEarlier, in 1781, I could have seen the Marquis de Lafayette and his lieutenants entering a Church Street hostelry to dine after leaving their American troops bivouacked across Spa Creek from Annapolis.

brbrEven earlier, in 1774, in a popular inn on upper Church Street called the “Coffee House,” you might have encountered, on his way to Williamsburg, one Patrick Henry, a Virginia assemblyman held high in esteem by all those who sought independence from Great Britain.

brbrIt was Henry, who on March 23, 1775, would speak those words that would stir his compatriots then and stir most of us as far back as Grammar school:

brbr“Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!”

brbrWith such a time machine, I could jump forward to 1789 and watch the 10-year-old Francis Scott Key cross Church Street on his way to King Williams School, which would become St. John’s College, from which Key would graduate as one of its accomplished academics and amateur poets and a soon-to-be lawyer. This same young man would find himself in 1814 watching “bombs bursting in air that gave proof through the night that our flag was still there” on a ship off Baltimore’s Fort McHenry.

brbrMore personally, I could see back to around 1730 and watch my great-great-great-great-great grandfather Burden Crosby, Commander of “The George,” bring his ship into the Annapolis harbor, picking up tobacco to transport to London.

brbrOur mythical time machine could also show ancient sights you might not like to see. Besides ships that brought some of the nation’s founders to Annapolis and ones that carried tobacco to England returning with all types of goods, you would see ships of agony docking in Annapolis harbor – slave ships that brought to America chained, sickened Africans such as famed author Alex Haley’s ancestor, Kunta Kinte, immortalized in Haley’s book Roots.

brbrOne of the most inspirational scenes we could view through our window time machine would be that of a large white horse carrying a tall man, with powdered hair and militarily dress with a cape over his shoulder to fend off the December 23, 1783 chill, leaving a Church Street hotel for the State House. The man was George Washington, on his way to take the momentous action of resigning his commission as Commander In Chief of the Continental Army, a decision described by one biographer, and echoed by many, as “the most significant address ever delivered to a civil society.”