×

By Stephen Perraudbr

brFor Annapolitans who came of age in the early 1990s, the stories still swirl and occasionally resurface. A neglected mansion, rich in history, left to rot before being repurposed by artistic and ambitious youth, eventually meeting its demise as a gathering place amidst a contentious police incident. For Ruben Dobbs, a career musician, discovering The Mansion, as it came to be known, as a wide-eyed 16-year-old was a revelation. “It was freaky pulling up to it. There were no houses next to it, just a mailbox on the road,” he said. “It was just this creepy mansion. Inside, [there was] loud music and people anywhere between my age and 50 hanging out, partying and having fun.”

brAside from the mix in ages to be found mingling at its parties, the property was also known to host an eclectic hodgepodge of revelers. “On any given night you would have hippies, rednecks, metal heads, rappers, college kids, and preppy Annapolitans,” says Dave Tieff, a regular at the house’s parties in the early 1990s.

The band Laughing Colors would often frequent and occasionally perform at The Mansion in Crownsville.brYears after his first experience as a teenager at The Mansion, Dobbs would come to encounter the property again in the spring of 1994, this time as a 20-year-old, playing guitar in different bands around the area and eventually joining up with a group called Yol Bolson. One of the band’s founding members—a reportedly mysterious, charismatic character that Dobbs and former Yol Bolson drummer Michael Kirby have, in the interest of maintaining his anonymity, dubbed Von Frugalvich—had moved into the notorious property.

The band Laughing Colors would often frequent and occasionally perform at The Mansion in Crownsville.brYears after his first experience as a teenager at The Mansion, Dobbs would come to encounter the property again in the spring of 1994, this time as a 20-year-old, playing guitar in different bands around the area and eventually joining up with a group called Yol Bolson. One of the band’s founding members—a reportedly mysterious, charismatic character that Dobbs and former Yol Bolson drummer Michael Kirby have, in the interest of maintaining his anonymity, dubbed Von Frugalvich—had moved into the notorious property.

With the previous tenants on their way out, Dobbs and Kirby became a part of the Mansion’s new crew of residents. The early days of residency were primitive, even for young men between the ages of 20 and 22. With no working plumbing or running water, Mansion residents were forced to embrace the great outdoors as a bathroom and given free run of the outdoor faucet next door at Rudy’s Tavern (now Rams Head Roadhouse).

With the previous tenants on their way out, Dobbs and Kirby became a part of the Mansion’s new crew of residents. The early days of residency were primitive, even for young men between the ages of 20 and 22. With no working plumbing or running water, Mansion residents were forced to embrace the great outdoors as a bathroom and given free run of the outdoor faucet next door at Rudy’s Tavern (now Rams Head Roadhouse).

brAs the band members worked on rehabbing the decrepit property, arming casual visitors with brushes and buckets of white paint, it became clear that Von Frugalvich had “a lot of ambition and vision for the place,” says Dobbs. This ambition manifested itself in the building of a fully functioning recording studio on the second floor. Taking to the road and selling balloons of nitrous oxide (laughing gas) in the parking lots of Grateful Dead shows, The Mansion crew easily covered their $250 (total!) monthly rent, parlaying all leftover profits into studio equipment.

“We had a great connection to ‘illegal air’,” Dobbs recalls. Nitrous oxide, a chemical routinely administered by dentists during oral surgery, is an oft-abused party drug. Since the gaseous chemical is also used commercially in food preparation, its possession and sale is almost wholly regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. While possession of nitrous oxide is not illegal, sale of the compound can be prosecuted under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act. The drug, readily available to The Mansion crew in large tanks, was an integral part of the parties and concerts held at the property, the latter of which began to grow in size of crowd and acts.

“We had a great connection to ‘illegal air’,” Dobbs recalls. Nitrous oxide, a chemical routinely administered by dentists during oral surgery, is an oft-abused party drug. Since the gaseous chemical is also used commercially in food preparation, its possession and sale is almost wholly regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. While possession of nitrous oxide is not illegal, sale of the compound can be prosecuted under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act. The drug, readily available to The Mansion crew in large tanks, was an integral part of the parties and concerts held at the property, the latter of which began to grow in size of crowd and acts.

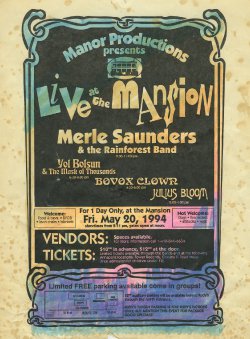

brWith a $5,000 budget, inflated by nitrous oxide sales, and the help of a friend who had experience in event management and maximizing parking efficiency, Dobbs and the rest of the crew were able to produce a performance at The Mansion by now-deceased legendary keyboardist Merl Saunders. “At that time, we could host between 500 and 1,000 people,” Dobbs says. The crew barely broke even on the Saunders performance, but the experience in production set them up for larger future endeavors. Meanwhile, the house’s ever-expanding recording studio allowed a handful of local bands in the area’s burgeoning music scene to cut demos.

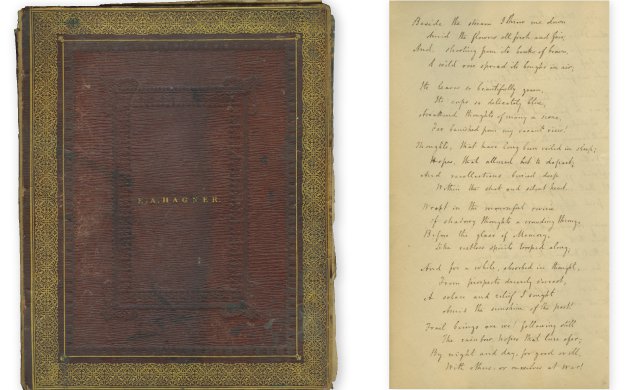

brOne day during the summer of 1994, as the band renovated the studio, they uncovered the diary of Eliza A. Hanger, a woman working in the 1800s for the wealthy Inglehart family. Hired to educate the Inglehart children, Hanger’s diary contained anecdotes about the property during her time, including flowers pressed and preserved into pages of the book from species of plants that still grew on the aging property. The Inglehart family, according to the diary, maintained the property as a summer home while residing in a huge estate on the South River. Hanger, along with other members of the family, is buried on a hill near The Mansion.

brShortly thereafter, in a completely random encounter resulting in an amazing stroke of luck, accomplished British producer and manager Richard James Burgess visited a Subway in Arnold for lunch. Spotting a young man appearing to be in the loop musically, Burgess asked what kind of music scene could be found in the area. The young man, a friend of Mansion residents, directed Burgess to the house, where Annapolitan favorites and Mansion regulars Jimmy’s Chicken Shack had been busy recording their second demo.

brIn September of 1994, with the experience of several large scale concerts at The Mansion under their belts, the Yol Bolson members began planning a large scale, two-night festival at the property. As the event’s logistics were mapped out, house members and friends handed out flyers in area parking lots to help spread the word. It wasn’t long before police officers caught wind, cautioning those handing out flyers that the event was ill-advised. Without a permit or the proper time to apply for one, the officers warned the event would be shut down.

brWith the arrival of the event, billed for September 22nd and 23rd, 1994, the residents were able to handle its early logistics well, as they had in past events at The Mansion. Attendees had been crammed into every possible spot, with tents and camping provisions set up everywhere in preparation for a multi-day music festival featuring local bands. Before the final act of the first evening, a police officer arrived on the scene, helping Dobbs, who had been waving cars along, to direct traffic. Shortly thereafter, in a moment that would spark near-pandemonium, a group of young men reportedly began harassing a lone attendee, who brandished a gun.

The diary of maid Eliza Hanger, which dated to the 1800s was discovered in the home during renovations.brWithin minutes of someone shouting about a gun, 12 police cars and two police helicopters were on the scene, advising attendees to leave immediately. Kirby, who stood and watched the mayhem, reportedly confronted a police officer who allegedly manhandled a young woman, pushing a boot into her back forcefully on the front porch of

The Mansion.

The diary of maid Eliza Hanger, which dated to the 1800s was discovered in the home during renovations.brWithin minutes of someone shouting about a gun, 12 police cars and two police helicopters were on the scene, advising attendees to leave immediately. Kirby, who stood and watched the mayhem, reportedly confronted a police officer who allegedly manhandled a young woman, pushing a boot into her back forcefully on the front porch of

The Mansion.

brArrested shortly thereafter along with Von Frugalvich and several unfortunate bystanders, Kirby was taken to the South County Precinct and booked on charges of disorderly conduct in a public place, disturbing the peace, and disorderly house, a charge that Kirby still finds outrageous.

brKirby’s father, a criminal defense attorney, helped him beat each charge in court. Von Frugalvich, who faced more difficult legal scrutiny because he had signed a lease for the property, eventually, beat his charges as well. But according to Kirby, the lasting scar of mistrust of authority and increasing paranoia took a heavy toll on Von Frugalvich, who later descended into drug addiction and eventually served significant jail time for unrelated charges.

br“I think it really took a toll on his self-esteem,” Kirby said of Von Frugalvich’s September 1994 arrest.

brFor Dobbs, the lasting impressions of The Mansion days are much rosier. Focused on the skills everyone acquired in recording music in the studio and producing live shows, he rattles off the paths on which some of the residents later embarked.

“It was my first introduction to production. I became a house engineer at Rams Head, I’ve been on the road with Hall and Oates, Bruce Springsteen…I’ve done production with them. I managed Jimmy’s Chicken Shack tours for a while. I credit the experiences [at The Mansion], that first little taste of production, it was a lesson on everything you need to know for a show,” he says.

“It was my first introduction to production. I became a house engineer at Rams Head, I’ve been on the road with Hall and Oates, Bruce Springsteen…I’ve done production with them. I managed Jimmy’s Chicken Shack tours for a while. I credit the experiences [at The Mansion], that first little taste of production, it was a lesson on everything you need to know for a show,” he says.

br“One of the other guys [from The Mansion] is high up in Paul Reed Smith guitars, one of the other guys still works with Bruce Springsteen,” Kirby says. When it comes to Von Frugalvich, Dobbs still hears “occasional tales.”

br“He’s still breathing,” he says. “As all geniuses do, he had his fair share of demons to deal with.”

brToday, The Mansion remains intact and has been meticulously restored and improved upon with modern amenities. Sitting on two-and-a-quarter acres, the private residence recently sold for $686,000 in April of last year. And though the musical mayhem, wild parties, and counterculture lifestyle have long since ceased, the memories and stories of The Mansion live on whenever the residents, band members, and attendees recall the time of their lives.

brFor Annapolitans who came of age in the early 1990s, the stories still swirl and occasionally resurface. A neglected mansion, rich in history, left to rot before being repurposed by artistic and ambitious youth, eventually meeting its demise as a gathering place amidst a contentious police incident. For Ruben Dobbs, a career musician, discovering The Mansion, as it came to be known, as a wide-eyed 16-year-old was a revelation. “It was freaky pulling up to it. There were no houses next to it, just a mailbox on the road,” he said. “It was just this creepy mansion. Inside, [there was] loud music and people anywhere between my age and 50 hanging out, partying and having fun.”

brAside from the mix in ages to be found mingling at its parties, the property was also known to host an eclectic hodgepodge of revelers. “On any given night you would have hippies, rednecks, metal heads, rappers, college kids, and preppy Annapolitans,” says Dave Tieff, a regular at the house’s parties in the early 1990s.

brAs the band members worked on rehabbing the decrepit property, arming casual visitors with brushes and buckets of white paint, it became clear that Von Frugalvich had “a lot of ambition and vision for the place,” says Dobbs. This ambition manifested itself in the building of a fully functioning recording studio on the second floor. Taking to the road and selling balloons of nitrous oxide (laughing gas) in the parking lots of Grateful Dead shows, The Mansion crew easily covered their $250 (total!) monthly rent, parlaying all leftover profits into studio equipment.

brWith a $5,000 budget, inflated by nitrous oxide sales, and the help of a friend who had experience in event management and maximizing parking efficiency, Dobbs and the rest of the crew were able to produce a performance at The Mansion by now-deceased legendary keyboardist Merl Saunders. “At that time, we could host between 500 and 1,000 people,” Dobbs says. The crew barely broke even on the Saunders performance, but the experience in production set them up for larger future endeavors. Meanwhile, the house’s ever-expanding recording studio allowed a handful of local bands in the area’s burgeoning music scene to cut demos.

brOne day during the summer of 1994, as the band renovated the studio, they uncovered the diary of Eliza A. Hanger, a woman working in the 1800s for the wealthy Inglehart family. Hired to educate the Inglehart children, Hanger’s diary contained anecdotes about the property during her time, including flowers pressed and preserved into pages of the book from species of plants that still grew on the aging property. The Inglehart family, according to the diary, maintained the property as a summer home while residing in a huge estate on the South River. Hanger, along with other members of the family, is buried on a hill near The Mansion.

brShortly thereafter, in a completely random encounter resulting in an amazing stroke of luck, accomplished British producer and manager Richard James Burgess visited a Subway in Arnold for lunch. Spotting a young man appearing to be in the loop musically, Burgess asked what kind of music scene could be found in the area. The young man, a friend of Mansion residents, directed Burgess to the house, where Annapolitan favorites and Mansion regulars Jimmy’s Chicken Shack had been busy recording their second demo.

brWith a handful of demos already recorded in their studio, Von Frugalvich and Jimmy’s Chicken Shack front-man Jimi Haha were able to play several bands for Burgess. According to Dobbs, Burgess “pretty much became [Jimmy’s Chicken Shack’s] manager on the spot.” The band would go on to garner significant airplay on MTV in the late 1990s for their hit single “Do Right,” with a significantly varied lineup than their Mansion days.

brIn September of 1994, with the experience of several large scale concerts at The Mansion under their belts, the Yol Bolson members began planning a large scale, two-night festival at the property. As the event’s logistics were mapped out, house members and friends handed out flyers in area parking lots to help spread the word. It wasn’t long before police officers caught wind, cautioning those handing out flyers that the event was ill-advised. Without a permit or the proper time to apply for one, the officers warned the event would be shut down.

brWith the arrival of the event, billed for September 22nd and 23rd, 1994, the residents were able to handle its early logistics well, as they had in past events at The Mansion. Attendees had been crammed into every possible spot, with tents and camping provisions set up everywhere in preparation for a multi-day music festival featuring local bands. Before the final act of the first evening, a police officer arrived on the scene, helping Dobbs, who had been waving cars along, to direct traffic. Shortly thereafter, in a moment that would spark near-pandemonium, a group of young men reportedly began harassing a lone attendee, who brandished a gun.

brArrested shortly thereafter along with Von Frugalvich and several unfortunate bystanders, Kirby was taken to the South County Precinct and booked on charges of disorderly conduct in a public place, disturbing the peace, and disorderly house, a charge that Kirby still finds outrageous.

brKirby’s father, a criminal defense attorney, helped him beat each charge in court. Von Frugalvich, who faced more difficult legal scrutiny because he had signed a lease for the property, eventually, beat his charges as well. But according to Kirby, the lasting scar of mistrust of authority and increasing paranoia took a heavy toll on Von Frugalvich, who later descended into drug addiction and eventually served significant jail time for unrelated charges.

br“I think it really took a toll on his self-esteem,” Kirby said of Von Frugalvich’s September 1994 arrest.

brFor Dobbs, the lasting impressions of The Mansion days are much rosier. Focused on the skills everyone acquired in recording music in the studio and producing live shows, he rattles off the paths on which some of the residents later embarked.

br“One of the other guys [from The Mansion] is high up in Paul Reed Smith guitars, one of the other guys still works with Bruce Springsteen,” Kirby says. When it comes to Von Frugalvich, Dobbs still hears “occasional tales.”

br“He’s still breathing,” he says. “As all geniuses do, he had his fair share of demons to deal with.”

brToday, The Mansion remains intact and has been meticulously restored and improved upon with modern amenities. Sitting on two-and-a-quarter acres, the private residence recently sold for $686,000 in April of last year. And though the musical mayhem, wild parties, and counterculture lifestyle have long since ceased, the memories and stories of The Mansion live on whenever the residents, band members, and attendees recall the time of their lives.