Ribbon cutting on June 14, 2017 of The Hall of Presidents Before Washington exhibit. Photo by Tony Lewis Jr.

It was an odd pop-up screen, I remember thinking—even for a pop-up screen—that appeared when I was searching online for the National Portrait Gallery’s Hall of Presidents in 2012: “Who was the first President?” I was given three choices: George Washington, Samuel Huntington, and John Hanson. “Who?” I thought, not recognizing the last two choices. “Was this some kind of a joke?” I was sufficiently curious, but I surprised even myself by making a selection, not knowing what to expect and mostly wondering if anything would happen at all. I had no idea that my life was about to change forever. It never occurred to me that answering one single question on one particular pop-up screen would have a profound effect on my career as an instructor of American Government.

What happened next, just a few seconds later, was a magical experience: I was transported to a long-forgotten time in the history of the United States, when Congress was unicameral; when presidents held a seat in the legislature like a Prime Minister; when the first constitution, the Articles of Confederation, prevented Congress from levying taxes or accumulating a deficit; and when political parties not only didn’t exist, they were discouraged by the Founding Fathers. I soon discovered that there were eight cities that served as the capital of this country before Washington, D.C., including Annapolis. And when George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of American armed forces, had resigned from the military (in Annapolis), he had written a letter of resignation to a Mr. President named Thomas Mifflin, one of fourteen separate men who held the title of “president;” in Mifflin’s case, six years before George Washington.

I also found out that Annapolis was the “next step” city. When French and American troops mustered at St. John’s College in 1781, the next step was their arrival in Yorktown, Virginia, and the surrender of Lord Charles Cornwallis to General George Washington. When the 1783 Treaty of Paris was ratified by Congress on January 14, 1784, the next step was an exchange of treaty ratification documents back in Paris on May 7, 1784, which concluded with the formal recognition of American independence by the British. When Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and ten other delegates from five states wrote a formal report to Congress on September 14, 1786, from Mann’s Tavern in Annapolis that explained how the inability of Congress to raise revenue through taxes would result in a default of American war debts, the next step was the Constitutional Convention.

I had learned more about American history in twenty minutes than I had in my entire life, and I had only scratched the surface! I scrolled down to the bottom of the page, searching for some rational explanation for how so much secret knowledge could have been kept from me all these years. It didn’t take long to get an answer: I had entered the enchanted world of Stan Klos.

Thomas Mifflin was one of fourteen

separate men who held the title of

“president;” in Mifflin’s case, six

years before George Washington.

He was the only American president

to serve in Annapolis.

The first version of the United States consisted of independent and sovereign “miniature nation-states” united by and dependent on a less powerful (than them) Congress that arranged their internal trade, external commerce, and collaborative defense; what one might describe as a sort of combination of NAFTA and NATO. In many ways, this model of the United States was a prototype of what we see when we look at what we call today the European Union, more of a regional entity than a national one. A fractured United States led by legislative presidents does not fit the modern narrative that describes the emergence of a single country under a federal Constitution led by a powerful president separate from but equal in power to a bicameral legislature and an independent judiciary. As a result, this history has been all but expunged from today’s K–12 curriculum.

Stan Klos decided that he wanted to do something about that, and his self-immersion into the events within the documents and artifacts that he collected made him one of the nation’s foremost experts on this time period as well as the historical documents trade. He has parlayed his immense knowledge in these fields into a still-growing private enterprise that includes countless books, an overwhelming demand for his lectures, and his exhaustive arrangement of traveling exhibits containing his ever-increasing personal collection of historical documents, now numbering in the hundreds.

The story of Stan Klos perfectly illustrates how an innocent foray into forgotten historical sites can lead to a growing interest in the events that transpired on those properties and a subsequent personal commitment to retelling those stories within the wider goal of saving the building. In 1853, women who would later become the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association became inspired to save the home of George Washington.

Now, in 2017, Mount Vernon is more than a restored home; it is the site of an impressive Visitors Center; a modern, computerized, interactive exhibit of Washington’s life; a gift shop; a food court; a restaurant; a presidential library; and a year-round schedule of daily events.

Annapolis Town Crier Fred Taylor delivers a proclamation

at the exhibit opening.

Think of how many people each day walk past the gravel pit on their way to the Noah Hillman Parking Garage not knowing that the call for what became the Constitutional Convention came from behind that fence. Because he brings the physical components of forgotten history with him, Klos is often able to persuade skeptical historians to re-examine their position on the pre-Constitution time period, hoping to spark a desire to re-evaluate the importance of related artifacts and eventually agree to create a place to put them so that the public can see them and understand their significance.

This is exactly what Klos was hoping to achieve when he brought his traveling exhibit to the Governor Calvert House in Annapolis on November 26, 2012, for a three-day “National Continental Congress Festival” of lectures, films, walking tours, souvenir sales, and television coverage to commemorate the arrival of Congress on that day in 1783 and the many achievements they accomplished in Annapolis.

The 2012 National Continental Congress Festival awakened the Annapolis community to the realization that Congress met here; the first peace-time capital of the United Sates was here; George Washington resigned from the military, preserving civilian rule, here; the Treaty of Paris was ratified here; James Monroe served in Congress here; Thomas Jefferson was appointed to France here; James Madison and Alexander Hamilton called for a new Constitution here; an American president served here. President Thomas Mifflin, who accepted Washington’s resignation, signed the ratified Treaty of Paris, and issued Jefferson’s French appointment, was housed at the Maryland governor’s mansion that stood where the home of the Superintendent of the United States Naval Academy now stands, making Mifflin the only American president to serve in Annapolis (John Hancock was president when Congress was in Baltimore from 1776–77, making him the first American president to serve in Maryland).

When Klos left Annapolis on November 28, 2012, it sucked the historical wind out of Annapolis’ sails. People wanted to know more about the congressional session in Annapolis, the many things that took place here during that time, and the 14 presidents before Washington, whose color portraits had been so prominently displayed among Klos’ documents. Sadly, nowhere in Annapolis could a photocopy of the ratified Treaty of Paris or a document with its words be purchased. And nowhere outside of the Maryland State Archives could someone learn more about the resignation of George Washington or how the Treaty of Paris was ratified. At no store on Main Street or anywhere else could someone buy a t-shirt or a mug or even a key chain commemorating the Treaty of Paris, Washington’s resignation, or the 1786 Annapolis Convention.

A year after Klos left Annapolis, the ball finally got rolling when former Mayor Ellen Moyer encouraged the Brown brothers—Sam Steve and George—to purchase individually what became a unique collection of signed documents, one for each of the 14 presidents before George Washington. Like in 2012 for Klos’ traveling exhibit, I was asked to plan a second National Continental Congress Festival to showcase the Brown collection. It took place in the Masonic Lodge from September 11–14, 2013, in order to commemorate the 1786 Annapolis Convention.

Simultaneously, the Maryland State House Trust purchased George Washington’s handwritten resignation speech and began renovating the Old Senate Chamber where Congress had met in order to emphasize the momentous events that occurred there between 1783 and 1784. Also, Historic Annapolis, owners of the William Paca House, merged its museum and store and purchased the James Brice House. (James Brice had served as Mayor of Annapolis from 1782–83 while William Paca served as Governor of Maryland and the Treaty of Paris was being negotiated.)

The Brown brothers designed replicas of their original documents to be framed with color portraits and bios that explained who the presidents before Washington were and what was being authorized in the documents that they had signed, including a frame for Washington—containing a photocopy of his signed resignation speech—for historical context. The Maryland Inn then offered to house the framed replicas in a room down the hall from, fittingly, their Treaty of Paris Restaurant and open its doors to the public.

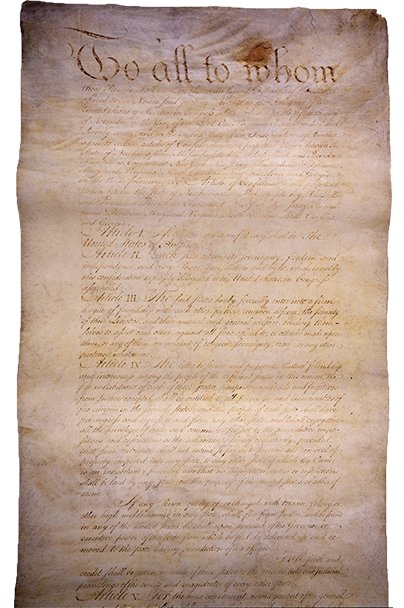

John Dickinson’s draft of the Articles of Confederation

named the new country “the United States of America”

and provided for a Congress with representation based

on population, and gave to the national government all

powers not designated to the states. Congress adopted

the Articles of Confederation on November 15, 1777.

During this time, Annapolis played a prominent role in bridging these two events by serving as the capital from 1783–84, sending delegates representing Maryland to the 1785 Mount Vernon Conference (resulting in an agreement between Maryland and Virginia to share the use of the Potomac River), and hosting the 1786 Annapolis Convention at Mann’s Tavern just after Shays’ Rebellion had begun. The Treaty of Paris Period is also the time when the United States tried and failed to pay off its Revolutionary War debts. A new Constitution became the only way to provide Congress with the authority to raise the revenue needed to pay its creditors. Without studying this crucial time in American history, the reasons for a new Constitution are lost and thus the important lessons about the dangers of financial default are forgotten.

Rediscovering how Annapolis came to be center stage during the Treaty of Paris Period requires a familiarity with both the limitations of the Articles of Confederation that contributed to the inability of Congress to pay its monetary obligations, and its strengths, including an absence of political parties, a unicameral legislature, presidents who were members of Congress, and the oversight powers over Congress held by the states such as granting permission to both go into debt and to go to war—powers that the states lost when the new Constitution was written.

The temporary home provided by the Maryland Inn offered a chance to gain that familiarity. Monthly events took place there in 2015, including appearances by noted Ben Franklin interpretive actor Christopher Lowell, a second National Treaty of Paris Festival in the fall, and a winter re-enactment of Washington’s resignation, complete with a dinner and a dance. Unfortunately, in 2016, the General Manager of the Maryland Inn was replaced and the room of replicas was locked, making it inaccessible to the public and launching an exhaustive search for a new home, which eventually led to the Westin hotel on West Street.

The framed replicas were removed from the Maryland Inn and re-installed at the Westin with additional documents, artifacts, and information panels as “The Hall of Presidents Before Washington” in time for the exhibit’s Grand Opening on June 14, 2017 (Flag Day). The collection included congratulatory remarks and awards for the Brown brothers by Annapolis Mayor

brMichael Pantelides, Anne Arundel County Executive Steve Schuh, and the office of Governor Larry Hogan, followed by lectures from Ambassador David McKean and Peter Hanson Michael, descendants of presidents Thomas McKean and John Hanson, respectively, who brought members of their families and books each man had written on their famous ancestors.

Now the question is, what’s next? A beautifully redesigned exhibit in

brsuch a modern facility in an aptly named part of Annapolis is fantastic, but it’s a very long walk to City Dock and the Visitors Center and thus the average tourist may not be sufficiently motivated to expend the necessary time and energy to come see it. There have been no further events at the Westin (at the time of this writing). Still, the remarkable development of this project since Stan Klos’ visit in 2012 cannot be overstated. There has been an explosion of books and websites about the 14 presidents before George Washington, the eight-year restoration of the Old Senate Chamber at the Maryland State House looks fabulous, and three successive Annapolis mayors have promoted this history and encouraged the public to participate in various related events over the past five years.

The biggest obstacle to the creation of a permanent home in Annapolis for the history of the Articles of Confederation era (one that is comparable to the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, with interactive exhibits, auditoriums for lectures, films, and traveling exhibits, and the availability of related souvenirs) is the unwillingness of the established historical community in Annapolis to collaborate with “amateur historians” toward such a goal.

Dignitaries celebrate the opening of the The Hall of Presidents Before Washington

exhibit at the Westin hotel in June of last year.

This brings me back to why I wish I had known that clicking on Stan Klos’ pop-up screen would change my life, because when Klos left, I became the face of this project. However, I cannot create a permanent, independent home for this historical period by myself because it requires a building, zoning, funding, and a long-term vision, and those are resources that only state and local government can provide. Until it is agreed that Annapolis should not be merely one more important historical city on the national map but instead the national capital of the pre-Constitution period—with the same kind of singular focus that has made Washington, D.C., Gettysburg, Philadelphia, and Boston must-see stops for domestic and international tourists—all of the new exhibits, renovations, and good intentions will not achieve the most important goal of all, that every student in the United States learn that Annapolis served as the bridge between the Revolution and the Constitution by providing a place where the new nation could grow, learn from its mistakes, and ultimately realize that it needed to create a more perfect union.

Mark Croatti is the Director of The Hall of Presidents Before Washington at the Westin hotel (www.presidentsbeforewashington.org). He teaches Constitutional Development at The United States Naval Academy and Comparative Politics at The George Washington University.