By Marimar McNaughton

Almost 51 years ago Cambridge, Maryland, was thrust into the national spotlight when blacks and whites took their angst and anger into the streets of the town’s Second Ward. Mayor Victoria Jackson-Stanley and Civil Rights leader Gloria Richardson recall the events leading up to the night of July 24, 1967.She was told to stay inside the house, Cambridge Mayor Victoria Jackson-Stanley remembers.

“Being the good ‘do bee’ that I am, I followed my parents’ instructions. My sister tells me she snuck out of the house and went on Pine Street, but once the trouble started she hightailed it home. There were National Guards all over the place, so I don’t know how she did that.”

From their second floor Park Lane bedrooms, about a block and one half away, Jackson-Stanley, then 13 years old, and the eldest of four children, says, “My younger brothers and I, and my mother, were ... looking over the rooftops of the houses next door. I remember seeing flames ... fire just shooting up from over top of the houses where we lived.”

On Pine Street, the hub of the Second Ward’s business district, fire had engulfed an old grammar school, a church, and a motel where H. “Rap” Brown, then the leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) rallied a gathering of 400–500 residents. Brown was invited back to town by Cambridge Movement leader Gloria Richardson, who was asked by the Cambridge Black Action Federation to send someone to speak to them about Black Power and what that meant, Richardson says during a 2017 interview.

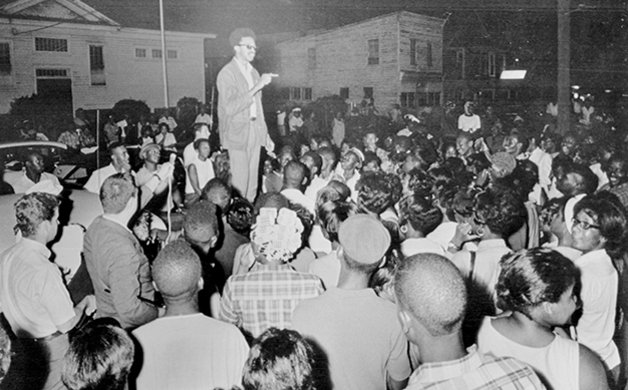

H. Rap Brown, student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee leader, speaks to crowd of about 250 in Cambridge on July 24, 1967. Brown, fresh from the Black Power conference in Newark, N.J., stood atop a car to urge militant action. Photo by Bettman/Getty Images

In archived audio files, it’s possible to hear Brown’s words echoed by cheers and applause.

A few weeks before Brown returned to Cambridge, a town he visited at the onset of the Civil Rights Movement in the early 1960s, a rash of small fires were set inside a vacant Second Ward schoolhouse, Richardson says. Because of those incidents, she warned Brown not to speak of burning things. But the call to action by burning was more than hyperbole for Rap Brown. It was one of his themes.

“If Cambridge don’t come around, we are gonna burn Cambridge down!” He shouted to his constituents from atop the hood of an old Buick parked on the street in front of a black-owned motel.

Brown’s voice—as uniquely his own as his fingerprints were when inked during his arrest on inciting a riot and other charges a couple of days later—was rhythmic, deliberate, rhetorical. He challenged Cambridge blacks to take what was rightfully theirs—namely the streets that were given to them—and the homes and businesses that were owed to them. And guns, go get some guns, he said. His intoxicating words excited the crowd, but he did not actually start the fire that engulfed the motel, the old schoolhouse, and a nearby church, before quickly spreading to other buildings on Pine Street.

“Two Blocks of Second Ward Burned During Night of Intense Racial Riots,” headlined The Daily Banner, July 25, 1967.

Richardson, whose Civil Rights career was cemented during the nonviolent years says, “If they come to your home and try to destroy that, you have to defend yourself.”

With zero population growth since 1967, Cambridge residents then and now number between 12,000–13,000, and the county seat of Dorchester on the Eastern Shore was and still is a prime hunting area where folks own rifles, shotguns, and BB guns. Those hunting guns were the same guns drawn during decades of racial tension, Richardson recalls, dating back into the late 1930s, and escalating in the 1960s when whites drove through the streets of the Second Ward and fired on the black-occupied homes there.

“The men, at night, had to come out because they were riding cars through and shooting at people’s houses,” Richardson says.

The July 25, 1967, Daily Banner carried the news of arson and looting, and the fire department’s refusal to enter the Second Ward.

“Firefighters—including volunteers and fire units from Easton, 16 miles distant—at first refused to enter the ravaged Second Ward. They went in about 5 a.m.,” wrote John Woodfield, Associated Press reporter. “Atty. General Francis B. Burch, after pleading in vain with members of rescue fire companies to enter the Second Ward, finally accepted a profane challenge, donned a firefighter’s coat and hard hat, climbed beside the driver of a hook and ladder truck, and moved into the area,” Woodfield reported. “The action came after two Negroes, who were brought out of the area by two Negro policemen, wept and pleaded with city police in vain to bring fire trucks into the area.”

Richardson’s family called her in New York City to say sparks were flying down by the Cambridge waterfront.

“I had General Gelston’s number, so I called him,” Richardson says. She and National Guard Adjunct General of Maryland, George M. Gelston, were close during their leadership years in the early 1960s.

“About two hours later, some of the press that had been in Cambridge in ’62 and ’63 and ’64, called me to tell me, that the Guard was on its way into Cambridge,” she says.

It marked the second time during the 1960s that the National Guard occupied the small Eastern Shore town.

Gathering on Pine Street, nearly 50 years after the incident, the Cambridge community’s black leaders and followers filled the pews and the aisles within Bethel A.M.E. Church one Saturday in February. Maryland Governor Larry Hogan had declared February 11th as Gloria Richardson Day and sent his Lieutenant Governor Boyd Rutherford in his stead to present the proclamation.

Everyone seated rose to their feet when the Cambridge Community Gospel Choir, backed by a rhythm section, launched into “Every Praise.” Mayor Jackson-Stanley was the first to honor Richardson, through the lens of personal memory.

“Looking up at this tall, beautiful statuesque woman more than 50 years ago, she was part of the Civil Rights Movement. As a little girl. I saw her and I thought, ‘Wow, that is a beautiful woman.’ I followed her, listening, sitting at the knees of my father, who was her lieutenant. I just marvel at the power of this woman. And as a young child, I didn’t get the significance of it at the time. But now I know what I was looking at, and how she modeled for me. This day is truly an outward symbol of how we value the wisdom and dignity of this woman. A woman who taught us to stand up and affirm what we knew was right—who took her time to teach us the hard lessons of life. Such as: stay focused; and believe when you stay focused your good work will be noticed. Today I’m a grown woman and I still look up to this tall, beautiful, stately woman, and I say, ‘Thank you Gloria Richardson Dandridge for the example you have set for us, for me and the city of Cambridge.’”

Jackson-Stanley’s comments and the others that followed during the annual Black History Month program offered a preview of what blacks and whites together might expect during Reflections on Pine—50 Years After the Fire, a four-day celebration planned by the Eastern Shore Network for Change that was held last July 20–23, when the memories of that night in July 1967 were revived by those who live to talk about it, and others whose lives were shaped by it.

H. Rap Brown speaks at a new

conference on July 27, 1967, three

days after inciting the Cambridge

protests, which turned into riots.

Twenty years after it began, The Cambridge Movement captured the attention of historian Dr. Peter Levy, author of the definitive “Civil War on Race Street.”

During a 2017 interview, Levy says, “It was unknown at the time and is still not that well known because it does not fit in the traditional way people either frame the movement as being southern or northern. The middle states get lost. Maryland gets lost in general.”

At that point in history when the nonviolent or heroic stage of the Civil Rights Movement morphed into the Black Power stage, Levy uncovered H. Rap Brown, Cambridge and “what I consider the heart and soul of The Movement—the early ’60s and Gloria Richardson’s leadership.”

These days Richardson’s memory is razor sharp. She recalls with great clarity her de facto leadership of the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee, or CNAC, and the events that took place 50 years ago and more. Her voice is soft, and peppered with laughter, but in photographs taken at the height of The Cambridge Movement her persona is fierce. In one iconic image, she is shown wearing a crisply ironed, tailored white blouse tucked into dungarees. Her jaw is set and her hand is raised near her chest as she pushes the bayonet end of a rifle away from her body.

“We were getting ready to march and had gone into a boot black shop with General Gelston,” Richardson says. “We were in there arguing. [He said] he had to stop us.”

She explains Gelston’s troops, populated by rural Maryland boys, rotated out every month or so during the National Guard’s 18-month occupation of Cambridge between 1963–64. The new troops called to duty did not understand the nuances of the relationship between CNAC and the Guard, or the mutual respect shared by Richardson and Geltson.

“They get antsy,” Gelston explained to her the day the photograph was taken. “I’d prefer you not march,” she recalls him saying.

“I went straight across the guard line. This man was trying to charge me. My adrenaline was high. The Guard—400 or 500 of them—were lined up across the street. I thought I heard bullets. I thought they fired on the crowd. John Lewis was there, two or three lines behind me, trying to organize a prayer circle. My thing was: ‘If they’re shooting, we need to go get something.’”

The Cambridge Movement was one of the local campaigns where blacks used nonviolent direct action during demonstrations, says Richardson’s biographer, Dr. Joseph Fitzgerald, via email in 2017. “When they went back to their neighborhoods and homes they used armed self-defense to protect themselves from terrorists who came into the Second Ward to assault them,” Fitzgerald says.

Mrs. Gloria Richardson (center), head of the Cambridge Non-violent Action Committee, and General George Gelston (left of center) of the Maryland National Guard, hold their arms in the air to halt a civil rights demonstration march on July 12, 1963. Later, after Gelston informed the demonstrators of the Guard’s ban on demonstrations under limited martial law, they dispersed. Photo by Bettman/Getty Images

CNAC’s success was hard won under Richardson’s leadership. But she never backed down until she had achieved what she wanted. Arrested multiple times by local police and at least once by the National Guard “for her own safety” during a 1964 riot protesting Alabama Governor George Wallace’s speech against the Civil Rights Act, she had traveled to Washington, D.C. five or six times to meet with U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to desegregate the local hospital, public schools and public accommodations, and provide 200 additional housing units and mandate the employment of black workers to build them.

Her landmark Cambridge Treaty of 1963, enacted into practice one year before the Civil Rights Act took effect, is the crowning achievement of her reign.

“The first signature was mine,” Richardson says.

Also signed by then Mayor of Cambridge, Calvin Mowbry; the city’s attorney and its chairman of the bi-racial commission; NAACP field secretaries; SNCC’s field secretary John Lewis; Attorney General of the State of Maryland Thomas Finan: Executive Assistant to the Governor Edmund Meser; Kennedy; and U.S. Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall on July 22, 1963, the effects were almost immediately felt in the hospital and the schools.

At the height of The Movement, Gloria Richardson bowed out of Cambridge. By the time she remarried and moved to New York City in 1964, the most influential Civil Rights leaders of the day had met her; marched the streets with her; and shared the stage with her, among them Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Congressman John Lewis, D-Georgia; SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael; and Malcolm X.

Of her election to the city’s highest office, Cambridge Mayor Victoria Jackson-Stanley says, “As a woman and an African-American, I’m overwhelmed. I think it shows just how much things have changed in Cambridge since the 1960s.”

Of the civil unrest she witnessed in her early teens, she reflects, “Have the wounds been healed and licked cleaned and everything is peachy-peachy? No, no,” Jackson-Stanley says. “There are those who lived through that experience that have the scars and the pain that they dealt with back then.”

American Civil Rights activists Gloria Richardson (nee St Clair, later Dandridge) (center, in white shirt) and Amelia Boynton (nee Platts, later Robinson, 1911–2015) (second right, in flower-print dress) lead a march of a pro-integration march, Cambridge, Maryland, May 1964. Photo by Francis Miller/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Jackson-Stanley ran against the establishment in 2008 and won her victory in a run-off election. Two terms into her career, she ran unopposed in 2016. Her office is located in what was a police station, and though she has no windows, her viewpoint is clear.

“My job as mayor is to present our best foot forward, to have people who have money, who have vision, to come to Cambridge now, while we’re rebuilding,” she says.

During the next three years, she hopes to create more recreation and cultural activities. She plans to brand Cambridge as a business-friendly community and is working with developers to redo properties. She wants to ensure the health of the Chesapeake Bay and the Choptank River and beautify the city beyond its main streets into every neighborhood.

“I want to revitalize Pine Street,” she says. “I want to encourage more entrepreneurship in the black community. The Harriet Tubman phenomenon is blowing up. I want to keep the life and legacy of Harriet Tubman in the forefront.”

Mayor of Cambridge Victoria Jackson-Stanley

reflects on the Civil Rights Movement and its

impact on the community she governs.

Photo by Tony Lewis, Jr.

"There are those who lived through that experience that have the scars and the pain that they dealt with back then.” –Victoria Jackson-Stanley

She met President Obama the day he signed the executive order for the Harriet Tubman National Byway.

“I want to make sure there’s no danger of that ever being changed. Lastly, I want to keep Cambridge a family-focused, friendly community. I’m not going to say Mayberry. We are not Mayberry. I don’t want to live in Mayberry. I want to live in a vibrant community—an interesting, exciting community.”

Richardson, now well into her 90s, says she visits Cambridge only once a year for the annual crab festival.

“When I was first Mayor,” Jackson-Stanley says, “she came in for something and I gave her the key to the city. She said she never thought she would live to see a black woman give another black woman, in Cambridge, the key to the city. That stuck in my heart forever.”