Why Sports Concussions Are Being Taken More Seriously

By Jake Russell

Fading away are the days when phrases such as “Walk it off!” and “Suck it up!” dominated the football lexicon at practices and games. Now terms such as “safety” and “long-term health” are taking precedence over the tough-guy persona that enveloped those who put on the pads of warriors.

With the National Football League leading the charge in concussion testing and proactively altering their rules for the sake of player well-being, the challenge of better protecting the ain in contact sports is becoming universally accepted.

In 2012, the NFL donated $30 million to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health to fund research for ain injuries and other health issues. In January, the NFL Players Association (NFLPA) announced a 10-year, $100 million research project between the union and Harvard University to study injuries related to football and the long-term damage those injuries cause. The NFL, NFLPA and the NCAA also have teamed up with USA Football (football's national governing body) to aid the “Heads Up Football” program, which promotes concussion awareness and proper tackling techniques (head up with both arms wrapped around the opponent, not head lowered to cause maximum contact with the helmet) to youth football players throughout the country.

Meanwhile, the NFL also is battling lawsuits from more than 4,100 former players who claim to have suffered head injuries while members of the league.

Dee Jones, associate head athletic trainer for Navy football and men's lacrosse, has seen a lot in her 26 years in Annapolis, but the progression in concussion awareness has impressed her. On a scale of one to 10, it's safe to say she feels confident about where concussion awareness and testing now stands.

“I feel like we're pretty high up there,” she says. “Eight, maybe. We're up there. Everybody's talking about it and people are continuing to educate about it.”

A common impediment to treating concussions is players concealing their symptoms. Jones says that is more prevalent in professional sports because it is their livelihood at stake and injury means loss of income. The desire to look tough, however, infiltrates all levels of athletes.

Jones explains that with the keen eye of the training staff and the help of teammates, these players can be discovered. “If a person is instinctively in a denial mode, that's also one of the indicators there's probably something wrong,” she says. “If they are trying to lie about it but they have an altered ain function, they're not going to be good at lying about it.”

Jones says that if a player got dinged and headed into a huddle but forgot the plays, teammates would take notice and alert the coaches or training staff.

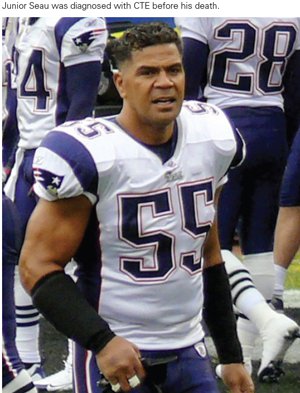

Brain injuries and the depression tied to concussions and repetitive head trauma have been linked to the suicides of former NFL players Junior Seau, Ray Easterling, Tom McHale, Andre Waters, Dave Duerson, and others.

Each of these men were diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which is defined by the Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy as “a progressive degenerative disease of the ain found in athletes (and others) with a history of repetitive ain trauma, including symptomatic concussions as well as asymptomatic sub-concussive hits to the head.”

Seau, 43, and Duerson, 50, were presumably so troubled by their ailments that their self-inflicted gunshot wounds were purposefully aimed at the chest in order to preserve their ains so they could be studied at Boston University.

Waters, who passed away in 2007 at the age of 44, was determined, by Dr. Bennet Omalu of the University of Pittsburgh, to have had ain tissue that deteriorated “to the level of an 85-year-old man” and showed comparable traits of early-stage Alzheimer's.

In 2010, researchers at Boston University found a link between concussions and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, more commonly referred to as ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease.

In the August 2010 episode of HBO's Real Sports it was reported that Gehrig suffered six serious head injuries during his time as a New York Yankee and these injuries may have led to his untimely death in 1941 at the age of 37. Gehrig, known as the Iron Horse, played 2,130 consecutive games—no doubt “playing hurt” in many of them.

The September 2010 issue of the Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology published findings from Boston University neuropathologist Dr. Ann McKee, stating she found the same toxic proteins in the spinal cords of three athletes who were diagnosed with ALS as in the ains of athletes diagnosed with CTE.

With the mounting evidence of the long-term effects of concussions, sports continue to evolve. Just as baseball players and cyclists resisted when wearing helmets became a requirement, adjustments have to be made for the sake of player safety. In 2011, the state of Maryland passed a law requiring that any athlete 19 years old or younger who is suspected of having a concussion must be removed from the game or practice for the rest of the day. The player can only return after being cleared by an appropriate licensed health care professional. This law applies to sporting events played on public school and parks and recreation complexes.